Even when it does something right, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) finds a way to turn it into a confrontation with federal law enforcement.

Even when it does something right, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) finds a way to turn it into a confrontation with federal law enforcement.

Since helping connect the families of five young Muslim men missing from the D.C.-area to law enforcement, the group has postured itself as an asset in the fight against extremism. CAIR's Executive Director Nihad Awad even described the "disturbing" farewell video the group's ringleader, Ramy Zamzam, left behind.

It "made references to the ongoing conflict in the world, and that young Muslims have to do something," Awad told reporters in December.

Somehow, Awad believes the good deed of advising relatives to go to the FBI gives him the power to demand that the five suspected terrorists be brought back to the United States and set free with nothing more than a slap on the wrist. If that doesn't happen, he has said repeatedly, there could be consequences.

As Awad said:

"Charging them and throwing them in jail is not the solution….The government has to show some appreciation for the actions of the parents and the community. That will encourage other families to come forward."

This is lunacy, as any review of the case shows.

The five young men, Zamzam, Umar Farooq, Waqar Khan, Amin Yemer, and Ahmad Mimmi, all lived within blocks of one another in Alexandria, Virginia. Last year, they contacted a Taliban recruiter via YouTube and exchanged communications in a draft email folder in a Yahoo account. After months of watching radical videos on the Internet, the men left Washington on November 28, leaving behind a videotape for relatives that showed scenes of American casualties and a speech by one of them talking about the need to defend Muslims.

Although their parents apparently did not know where their children had gone, they contacted the authorities to report them missing. By all accounts, they have continued to cooperate. As much as they deserve praise for these actions, it is important to remember that this is something that any parent would do upon learning of their kids' disappearance.

While the parents were trying to work with authorities to locate their children, the Zamzam Five were attempting to gain terrorist training in Pakistan.

Authorities say that the men traveled to Hyderabad, Pakistan. There, they were denied entry into militant training camps operated by Jaish-e-Mohammad and Lashkar-e Tayyiba, both designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations. They were eventually arrested on December 8, at the family home of Khalid Farooq Chaudhry, the father of one of the men.

After months of investigation, in both the United States and Pakistan, on March 17, the men were formally charged in a Pakistani anti-terrorism court in Sargodha. Among the charged offenses are conspiracy to commit terrorism in Pakistan and plotting attacks against a friendly country, both of which could result in life sentences. The men have pled not guilty and the expected six-month trial is set to begin on March 31.

Although U.S. authorities have not yet said whether they intend to seek extradition of the men to stand trial here, it remains a possibility that they may one day face other charges in America. Should they return to the United States, CAIR would like to see them set free. Such a step would be an extraordinary departure from both established principles and common sense.

While it axiomatic that federal prosecutors have broad discretion to decide what charges to bring, when to bring them, and where to bring them, it is highly unlikely that anybody in the Justice Department would find the cooperation of parents in locating their missing children to be a compelling enough justification to forego prosecution of suspected terrorists. Rather, the cooperation of family members should be given the same weight as it is normally given in criminal investigations—a mitigating factor to be considered during the sentencing phase of a trial. In at least two high-profile cases of domestic terrorism, the Justice Department took just that step.

From 1978 to 1995, Ted Kaczynski sent 16 bombs to targets including universities and airlines, killing three and injuring 23. After an FBI investigation spanning nearly two decades, the "Unabomber" wasn't caught until his brother tipped off authorities. Despite the cooperation of a family member, a federal grand jury indicted Kaczynski in April 1996 on 10 counts of illegally transporting, mailing, and using bombs. Although the Unabomber eventually pled guilty in exchange for a sentence of life in prison, his brother David was in negotiations with federal prosecutors to ensure that his cooperation would be considered as a mitigating factor as sentencing.

Similarly, Stephen John Jordi, a religious fundamentalist who was accused of plotting to fire bomb abortion clinics, churches, and gay bars, was turned in to authorities by relatives. Rather than demand that he not be prosecuted, his family spoke at Jordi's sentencing hearing, and he received the guidelines-minimum of five years.

CAIR is either willfully ignorant of these precedents or believes that this case is special. Yet Awad repeated his argument for leniency this week, hinting at trouble down the road if their expectations are not met:

"I think the outcome of this trial will determine how parents in the future will interact with the government."

Think about that. You find a farewell video from your son, who disappeared days ago. You have reason to believe he is in league with people bent on violence. What options do you, as a parent, have? Either go to the authorities in the hope they can find your child before it is too late, or roll the dice and hope the kid changes his mind and makes his way home.

Awad seems to be saying parents may opt to gamble on their children's lives. At the least, he suggests their cooperation is contingent upon a quid-pro-quo.

This takes CAIR's repeated exhortations to not cooperate with law enforcement authorities to a new extreme.

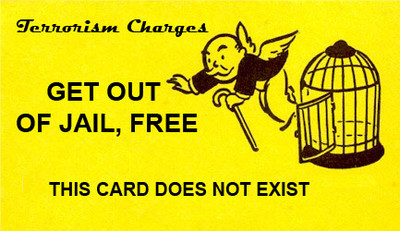

The suggestion that the only reasonable response to the cooperation of family members is a "get out of jail free" card is preposterous. Even if that were true, however, it's certainly a dangerous game of chicken in which CAIR suggests engaging.

If the Zamzam Five ever make it back to the United States, the crimes of which they have been suspected are simply too serious to be brushed under the carpet. They offered support to terrorist groups and conspired to kill American troops. According to authorities in Pakistan, police recovered maps of nuclear power plants and air force bases, the intended targets of the men. Even the group's alleged leader, Ramy Zamzam, has not denied their ultimate objective: "we are not terrorists…we are jihadists, and jihad is not terrorism."

The cooperation of their parents should be taken into account as a mitigating factor when they are brought to justice, but in no way should it immunize the men from prosecution.