Chesler Memoir Powerfully Illustrates Muslim Misogyny

Among the great joys of writing a book is the discovery, as you go, of what it really is about. Rarely does an author know from the beginning what she will discover before it ends.

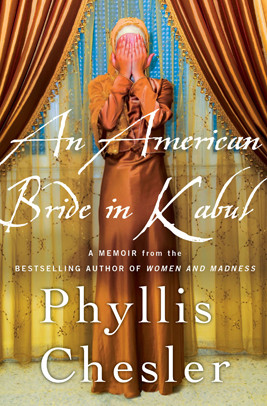

So it was for Phyllis Chesler, who set out to write An American Bride in Kabul as a memoir of her life as the young, Jewish-American wife of a wealthy Muslim in Kabul in the 1960s. By the time she'd finished, she'd penned something much more: an analysis of the plight of women in the Muslim world.

Chelser was a wide-eyed college student in 1961 when she met the man she calls Abdul-Kareem, scion of one of Afghanistan's wealthiest families. He was charming, elegant, romantic, and Muslim. She was a bright young Orthodox Jew from Brooklyn, eager for adventure, lured by the exotic. Abdul-Kareem offered both; and when he asked her to marry him and join him in his privileged life in his home country of Afghanistan, she joyously said "yes."

But the fantasy she envisioned was nothing like what she found once they arrived at his family compound in Kabul.

The first sign of this reality comes when she is ordered to relinquish her passport on arrival in Afghanistan, leaving her effectively stateless. As a woman, she is now property, belonging not to a nation or a people, but to the man to whom she's wed. And things will only grow more horrific.

Combining the treasured resources of her diaries, personal memories, and the insight born of years, Chesler takes us into the hidden chambers of the harem where she now lives, and the homes she shares with her mother-in-law, her father-in-law's other two wives, and various sisters-in-law and servants. Here, she lives in purdah – isolation – or what she more descriptively calls "imprisonment."

For the young Phyllis, this is nothing less than hell. She is not permitted out without an escort, and her new husband, entirely involved in building his own life and his role in Afghan society, is too preoccupied to take her anywhere. She speaks no Pashto, and despite her many requests, is not given any formal lessons. She longs to sit and read, but solitude is frowned on. More urgently, the ghee the servants cook with makes her ill, a situation that worsens when she contracts hepatitis and, in her weakened state, nearly starves to death. Through it all, her husband – that worldly, debonair intellectual she fell in love with in America – offers no sympathy whatever. He says she is "too impatient," "unreasonable," or – the standard phrase used by abusive husbands everywhere – "a bad wife." On top of this, she is too American, and her American-educated husband now has few kind words for America or the West.

The tragedy is that everything he says is true. She is American. She is impatient. She doesn't understand. And equally, despite his years in U.S. universities, he is not American; he is Afghan. And he, too, doesn't understand.

Had they both realized this situation, she would never have followed him to Afghanistan.

But they were young and in love, and the world was a different place.

Chesler grows desperate. A surreptitious trip to the American embassy proves fruitless: she has no passport, and is therefore trapped. The embassy staff cannot help. She begs her husband to leave Afghanistan, to set out on the travels and adventures they originally had planned, but he will have none of it. He is still caught up in his own future, his self-image, and the (probably imagined) role he will one day play as a leading figure in what he insists will be the rebirth and democratization of his country.

So wedded is Abdul-Kareem to this dream, that he begins his own campaign to force Phyllis to remain with him in Kabul: while she is weakened by hepatitis, barely able to move, he rapes her nightly. She suspects his purpose is to impregnate her: as a woman carrying a child, she would not be able to leave Afghanistan. And once the baby was born, to leave would be to abandon her own child. She writes:

"The husband who presumably loves me is willing to risk my death and the possibility of a deformed child – rather than risk losing his power over me or his honor. These are not things we ever discuss. These are my conclusions now, many years later. I may have loved Abdul-Kareem but I am now in a life-or-death situation. I discover that I love my life more than I love my husband. One never forgets such lessons, especially when one is privileged to learn them at a relatively young age. Abdul-Kareem begins to stay away from our bedroom until late at night. As the systematic attacks continue, Abdul-Kareem's oldest sister […] mercifully offers to sleep in our bedroom to help me during the night. She understands what is happening."

What Chesler didn't anticipate when she began this book was that it would help her to understand – and so help readers to understand – the ways in which the treatment of women in Afghan culture sets the stage for the tribal strife, the violence, and the insularity of Afghan culture as a whole. And it is precisely those conditions which, she suggests, inevitably helped create the often-backward, Islamist country it is today under the Taliban. Indeed, the author suggests that the misogyny endemic in Muslim society and fundamentalist Islam cannot but lay the groundwork for that kind of society. This is why so much of the Muslim world remains locked in a pre-Enlightenment era, battling poverty, illiteracy, civil strife, terrorism, and the right to human dignity.

Chesler's analysis of these intertwining threads and the fabric that they weave together forms the focus of the second half of American Bride. This kind of scholarly investigation is Chesler's strength, and it shows. The memoir section, while fascinating and at times quite gripping, reads awkwardly here and there as the scholarly, academic Chesler collides with Chesler the engaging storyteller. (The occasional interjection of such informal familiarities as "(!)" only adds to the awkwardness, unfortunately, and leaves the reader wondering where the editors were.)

But if one would wish for more of the storyteller Phyllis in Part I, it is the near- absence of that voice that gives Part II its gravitas.

Chesler did eventually escape Kabul (in a tale that is Hollywood-worthy) and return to her family in New York. Eventually, Abdul-Kareem remarried, and in time, was forced as well to flee Afghanistan, arriving in New York in 1979. Over the years, the two maintained occasional contact, and the transcripts of their various dialogues help lend form to Chesler's views. For those who are already familiar with her work as one of America's foremost feminists and as an expert on the subject of honor violence, these discussions also provide a window into Chesler's own development, and why, perhaps, she has chosen to pursue the causes for which she is best-known. More, they emphasize the cultural and ideological distances between the Jewish-American-born Phyllis Chesler and the Afghan immigrant who once had been her husband – distances that at times seem impossible to traverse. She ruminates:

"Looking back, knowing what I now know, I must ask: How could Abdul-Kareem have been so foolish, so blithe, as to have brought a Jewish American bride back to a country that had impoverished its small population of Jews and granted safe haven to German Nazis? Did he think that the rules of history would never apply to us? In 2011, Abdul-Kareem proudly told me that when he was the deputy minister of culture, he had negotiated treaties with UNESCO that would give 'landmark status' to ancient sites in Afghanistan…. In this context he had restored the synagogues of Herat and Kabul. They are all empty now. One has been converted into an Islamic school for boys. I tell him this. He says nothing. I ask Abdul Kareem, 'Why did the Jews leave Afghanistan?' 'Gee, I have no idea. Probably they up and left because they wanted to go to Israel anyway.' Like his mother before him, Abdul-Kareem claims to have no idea why Afghan Jews left Afghanistan. Is this sheer ignorance or deadly denial?"

The bigger question, though, is why that same man who cannot see how women are being abused, oppressed, caged in his culture is equally oblivious to the conditions Jews and other minorities experience in Afghanistan. And it's not just Abdul-Kareem; he is but a symbol for other, equally Westernized and educated men from Afghanistan and the Arab world.

Similarly, Chesler wonders why the same questions about ignorance or "deadly denial" seem to persist in the West, even among her own humanitarian and feminist colleagues. "While I praise the courage that has led so many Westerners to try to help Afghans survive day by day," she writes, "I am also frustrated beyond measure that so many of these humanitarians continue to blame America and the West, and refuse to understand the realities of indigenous gender and religious apartheid and the totalitarian evil we are facing."

She goes on to quote Leon Wieseltier, "The struggle for gender equality is the campaign against totalitarianism," and to conclude:

"The battle for women's rights is central to the battle for a Judeo-Christian, post-Enlightenment civilization."

Yet for all her strong-mindedness, Chesler writes with humility, modesty, and with the kind of reflection that can only come with years. Abdul-Kareem was not the only one to blame here: they were young and idealistic and giddily in love. Chesler also acknowledges her own failures, including perhaps the most important: neglecting to do her homework, to research before leaving for Afghanistan what her life would actually be there.

The passage of time (and the wisdom of age) has also helped her better understand Abdul-Kareem's position during their time in Kabul. And she has gained more sympathy towards his family, even expressing warmth for Bebegul, her hysterical, manipulative, anti-Semitic mother-in-law, whom she comes to see as a tragic figure, a woman imprisoned in a life with no love and little happiness.

What emerges is not just Phyllis Chesler's deepened understanding of the months she spent in Kabul – ultimately the most formative experience of her life. Nor is it just an opportunity for the author to present, in the clearest words possible, the vision and the ideology that have driven her work for decades. In the end, An American Bride in Kabul also reveals the fundamental force that drives her battles for women's rights, and especially for the rights of women in the Muslim world. For all the controversy she has raised over the years, hers is a mission born not of racism or anger or so-called "Islamophobia," as many have insisted, but of compassion and a real empathy – the kind that can only come from having lived through the experience herself. It is not hatred that brings her to this place, but love – love for women, yes, but also her own personal love for Afghanistan, and for the friends and family she left there. They will always be a part of her life; and it is for them and for their future, it seems to me, that she has written this invaluable and all-important book.

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands.