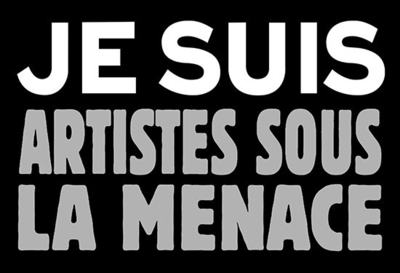

How well so many of us remember. It wasn't very long ago – barely eight months – since Muslim extremists stormed the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris, killing 12 of the satirical magazine's editors and artists. And how well we remember, too, the hours and days that followed as the world declared its support for free expression, with hashtags and marches and T-shirts and headlines that bore the now-immortal phrase "je suis Charlie" – and believed that it would make a difference.

How well so many of us remember. It wasn't very long ago – barely eight months – since Muslim extremists stormed the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris, killing 12 of the satirical magazine's editors and artists. And how well we remember, too, the hours and days that followed as the world declared its support for free expression, with hashtags and marches and T-shirts and headlines that bore the now-immortal phrase "je suis Charlie" – and believed that it would make a difference.

Apparently, it didn't.

Earlier this month, a group of Dutch Muslim youth surrounded actor Abbie Chalgoun – a self-described "non-practicing" Muslim – at a train station in Venlo. They called out, "Whore child! Just you wait. We know where you live. We know where to find you."

Chalgoun's misdeed? He plays the role of Jesus in a nationally-celebrated performance of "The Passion." For Muslims, Chalgoun explained in an interview with national daily Trouw, the image or personification of a prophet – including Jesus – is forbidden.

And so you think: here we go again. The concept of the arts for radical Muslims becomes nonexistent, and so, impossible. European civil laws for them possess no meaning and no power. True, unlike Chérif and Said Kouachi, the brothers who staged the attack on Charlie Hebdo, these youth have not (yet) committed a crime in this case, did not (yet) physically attack the 35-year-old actor. But they demonstrate clearly the subtle, more insidious threat that lurks in Europe today: a generation of Muslims who too often place Allah's law above the state, and who will use violence and intimidation to make the rest of Western civilization do the same. Sometimes – as with the attacks on a conference on free speech in Denmark last February or a draw Mohammed event in Texas in May, they will try to kill for it.

But sometimes the threat alone is enough.

Those who oppose his playing the role of Jesus comprise "no more than a half percent [of Dutch Muslims]," Chalgoun estimated, "but they are the ones with the biggest mouths."

They also follow a solid tradition among European Muslims, particularly in the Netherlands, where the Dutch-Moroccan Mohammed Bouyeri shot and stabbed writer and filmmaker Theo van Gogh to death in 2004, then plunged a knife into his body along with a lengthy letter that included a list of those he would attack next. Since then, there have been plenty of others, from artist Rashid ben Ali, threatened for his drawings of Mohammed and "idiot" imams; photographer Sooreh Hera, who received death threats for her photographs of costumed homosexuals she claimed depicted Mohammed and his son-in-law Ali; outspoken anti-Islam Parliamentarian Geert Wilders, whose film "Fitna," exposes the destructiveness and dangers of radical Islam; and even comedian Ewout Jansen, who was the target of threats against "those who make jokes about Islam."

To his credit, Chalgoum – like these others – has so far remained unbowed. ("Jesus was also threatened," he told Trouw.) So, too, is activist Pamela Geller, despite alleged plans by Boston-based Islamic terrorist Usaamah Rahim, who was killed in a confrontation with Boston police in June.

Not so, however, for far too many others – like the National Youth Theatre of London, which earlier this month cancelled a play about the radicalization of British Muslims, inspired, said its Muslim creators, by the plight of two British schoolgirls who joined the Islamic State earlier this year.

Tweeted one would-be cast-member, in frustration, "I don't know how anything can ever change when we are too scared to say the things that need to be said."

Perhaps the play's censors – among others – might take a lesson from Chalgoum, who told NPO radio shortly after the incident, "We can't let things like this make us crazy. We will go on. "

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands.