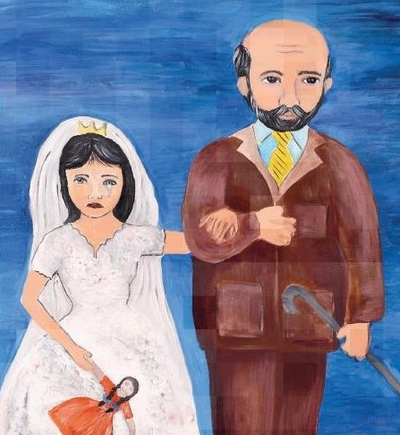

UNICEF graphic |

Yet for many of these refugees, married off against their will, the terror has already begun. They are 11 and 13 and 14 years old. Some of them are pregnant. Some are already mothers at 14. Their husbands are 25 or 38 or 40. And there is no escape.

"Child marriage existed in Syria before the start of the conflict," reports Girls Not Brides, a global partnership aimed at ending child marriage worldwide, "but the onset of war and the mass displacement of millions of refugees has led to a dramatic rise in the number of girls married as children."

Indeed, since the start of the refugee crisis, UNICEF reports, as many as "one-third of registered marriages among Syrian refugees in Jordan between January and March 2014 involved girls under 18," with some as young as 11.

In many cases, these marriages are set up by well-meaning parents who believe their daughters would be safer in the asylum centers if married and so, less likely to be approached sexually by strange men. In other instances, the daughters are sold off by parents who can no longer afford to keep them, or given in marriage to men already planning to leave Syria in the hopes that, once the couple arrives in the West, the parents can then legally join them.

But girls married in their early teens and younger face dark futures, according to Girls Not Brides. They are more likely to live in poverty, often are physically and emotionally abused, are at higher risk for sexually transmitted diseases, and are vulnerable to complications during childbirth – some of them fatal.

The plight of refugee child brides, which some authorities now call a crisis, first came to light in October last year, when 14-year old Fatema Alkasem vanished from a refugee center in the Netherlands along with her husband. She was nine months pregnant at the time.

Alkasem's disappearance led to an emergency session of Parliament, and the ratification of a long-delayed bill that would automatically dissolve the marriage of a minor, even if performed legally in the country where the nuptials took place. Under the revised law, the husbands of minors who continue living with their wives could be prosecuted for rape and deported. Where needed, the wives would receive special medical and psychological care and, wherever possible, placed in Dutch foster homes.

The impact of the case reached far beyond the Netherlands, where an average of three child brides arrives each week. With 15 million girls worldwide forced into marriage every year, and with child marriages among Syrian refugees skyrocketing, the problem of protecting these girls is now a global one.

But while the Netherlands has taken an aggressive stance to protect these young brides, who are often sexually abused, other countries are more circumspect, even as the crisis deepens. In Norway, for instance, officials determined in December that 61 underage migrants were already married when they arrived (including one 11-year-old girl). But it was the publicized tale of a 14-year-old girl arriving with her 18-month-old child and 23-year-old husband, also in December, that ignited public outcry and prompted new focus by the government on the issue. Police sought to prosecute the case on criminal grounds, noting that Norway's age of consent for sexual relations is 16. Yet others, such as feminist activist Unni Wikan, argued to the contrary, that Norway "might have to accept that underage refugees are married and have children." At this writing, the debate is still ongoing.

Opinions are also mixed in Denmark, where a January report of the country's asylum system revealed that 27 underage girls were married, including two 14-year-olds, one of whom was pregnant. Speaking to newspaper Metroexpress, conservative party spokesman Naser Khadir minced no words: "It's called pedophilia when a man gets a 14-year-old pregnant," he said. "We can give asylum to the 14-year-old, but we should kick the grown man out." The husband in this case is said to be 24.

In the interim, asylum-seekers under the age of 15 – Denmark's legal age of consent – are to be separated from their spouses and their cases reviewed by immigration officials.

But here, too, some believe that it is better to recognize such marriages. Prominent Danish imam Oussama El Saadi of Aarhus told Metroexpress that these marriages are "part of the culture" of the refugees, and so should be looked at "differently," according to the Copenhagen Post.

Whatever one thinks of such reasoning, there is one urgent argument to support the idea that Europe should recognize these marriages, or at least find alternatives to simply rejecting them: the risk these girls face of becoming the targets of honor killings, murdered by their estranged husbands or even their own parents. A young woman who has been married – and especially one who has given birth – is no longer seen as "pure" in strict Islamic culture, thereby sullying her family's reputation. The only recourse, in far too many Muslim families, is to cleanse the family through her blood – or murder. Even if she were to be spared such a fate, a Muslim man would be unlikely to marry her in future.

These are concerns European governments must consider in helping these young women.

In the Netherlands, officials already are taking the threat of honor killings seriously. In an e-mail, Parliamentarian Aatje Kuiken, a member of the Dutch labor party (PvdA) who was instrumental in changing the minority marriage laws, said that special teams have been set up to focus on the issue, and give the girls extra protection where needed. Hopefully, other countries will swiftly follow suit.

In Norway, however, officials are taking a different approach: providing classes for migrant men on the appropriate treatment of women. Such courses in European codes of behavior and ideas about sexuality and sexual norms, according to the New York Times, establish "a simple rule that all asylum seekers need to learn and follow: 'to force someone into sex is not permitted in Norway, even when you are married to that person.'"

Such classes currently are voluntary, suggesting that those men who most need them, those more inclined to insist on the social norms of their home countries, and who firmly maintain that their wives are their property, are actually the most unlikely to enroll. Still, the initiative offers hope and could provide a model for other states and the possibility of long-term progress – if not to change the lives of these young child brides, perhaps, one day, to change their daughters'.

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands.