Some weeks after the attacks of 9/11, a Dutch journalist spoke at a panel discussion in Amsterdam, describing his experience of the events. Faced with the task of writing up what had occurred in New York that day – the devastation, the terror, the unanswered questions that remained – he said he found himself completely overwhelmed. And then at a certain point, he recalled, clarity came. "I realized it was just about America," he said. "It had nothing to do with me."

Some weeks after the attacks of 9/11, a Dutch journalist spoke at a panel discussion in Amsterdam, describing his experience of the events. Faced with the task of writing up what had occurred in New York that day – the devastation, the terror, the unanswered questions that remained – he said he found himself completely overwhelmed. And then at a certain point, he recalled, clarity came. "I realized it was just about America," he said. "It had nothing to do with me."

I've told this story before, and likely will many times again, but it came to me as I read an op-ed by Daniel Benjamin in response to Tuesday's terrorist attacks in Brussels. Benjamin served as the State Department's counterterrorism coordinator from 2009-12. What happened in Brussels, he essentially declares, is really just about Europe. It has nothing to do with us. And it can't happen here.

I respectfully, but emphatically, disagree.

To be sure, Benjamin makes some important points. The background and immigration history of most European Muslims is not the same as that of Americans. Europe's Muslims largely arrived as guest workers in the 1960s and 70s from rural areas of the Middle East and North Africa (mostly Turkey, Algeria and Morocco). They were not educated; many were even illiterate. Because they were not expected to stay, their host countries did little to help them integrate, including teaching them the language.

But they did stay, and they brought family members from back home to live with them. They had children – many of them. And their children often suffered in school, where they were confronted with different values than their parents had, and with homework with which their parents could not help them. Many failed. Some had trouble getting jobs, and still do; Muslim unemployment all across Europe is significantly higher than the rate for non-Muslims.

By contrast, Benjamin notes American Muslim immigrants are largely well-off. Except for recent refugees, they come largely from the educated classes of their homelands, and have been therefore able to provide more support to their children.

Benjamin also correctly notes that significantly fewer American than European Muslims have made hijrah, or traveled to Syria to fight with ISIS and other jihadist groups. This is largely a consequence of geography. It is far easier to make the trip from Germany or Belgium to Turkey, and from there to Syria, than it is to make the same trip from, say, Michigan or New Jersey (both of which have large Muslim populations).

But those facts are not necessarily relevant to the threat of serious Islamic terrorism in America, or – as Benjamin would argue – the lack of one. Indeed, it is long past time to retire the old saw that says Muslims radicalize because of poverty, alienation, or disadvantage. American Muslims have, in fact, conducted plenty of terrorist attacks since 9/11 – among them, Nidal Hassan (of the Fort Hood shootings); Tashfeen Malik and Syed Farook (of the San Bernardino massacre); and the Tsarnaev brothers, who committed the Boston Marathon attack. Not one of them was impoverished or socially alienated. In fact, all were relatively comfortable financially, and well-integrated within their communities.

Similarly, Fouad Belkacem, the leader of Sharia4Belgium, an organization responsible for helping radicalize many Belgian Muslims, even laughed at a journalist once for assuming he must have come from a struggling background. His father was a car salesman and he once planned to take over the business, but his father retired early. And Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the alleged leader of the Paris attacks, reportedly attended a "posh" school, where, his former classmates recalled, "he was one of us."

Moreover, the demographics of Muslims in Europe are pretty much the same across the board; so if poverty and discrimination are the issue, why have there been no mass deaths from attacks in the Netherlands, say, or Germany – both of which border Belgium?

All of which may be why the Wall Street Journal once referred to the notion of "poverty as cause of terrorism" a bad idea that refuses to die, confirming the position expressed by Harvard economist Robert J. Barro and others.

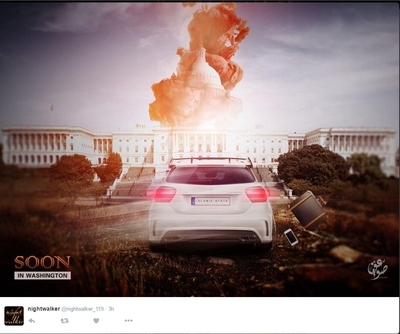

As for the argument about geography, this is precisely the genius of Islamic State leaders. It matters not that U.S. Muslims have a harder time traveling to Syria than do their European brothers and sisters. They are radicalized just the same way the Europeans are, on the Internet. In prisons. By recruiters already on the ground. Nor do they need military training in Raqqa; the instructions for bomb-making are online, freely available to anyone who wants them. Not to mention the easy availability of assault rifles.

But it is something else, deep at the core of Benjamin's argument, that is so disturbing: that the fact that fewer people have died in post-9/11 attacks in the U.S. than in Europe somehow suggests that America is less at risk, that Americans should not fear an attack like the ones in Paris in November, or Brussels on Tuesday.

He is wrong. Americans should fear exactly that.

It is insulting, this argument that because fewer people died in Boston than in Paris, say, the effect or the threat of the Marathon bombings somehow wasn't "quite so bad," that somehow it's okay, as if those killed and injured in America didn't matter quite as much, or as if the number of dead and maimed was the issue, and not the effort at killing and maiming in itself. And if it were, we may as well include 9/11, in which case America is way ahead in the body count game.

What is true, and Benjamin calls this one right, is that American counter-intelligence and security actions have been far superior to Europe's since 2001. American officials have foiled dozens of plots to date; but let's not forget that James Elshafay and Shahawar Matin Sira nearly bombed the New York Subway system a day before the Republican National Convention in 2004; that Faisal Shahzad came frighteningly close to blowing up Times Square in 2010; and that Mohamed Osman Mohamud had been spotted by the FBI well before he attempted to detonate bombs during a Christmas tree lighting ceremony in Portland, Oregon one month later.

After all, if your neighbor's husband beats her up twice a day, and your husband beats you only once, does that make the beatings any better? Does it take away the horror or the pain? Does it make you any safer?

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands.

So yes, terrorists have killed fewer Americans than Europeans since that bright September morning. But to suggest that Americans are somehow any safer is simply irresponsible.