She grew up in the college town, traveled the globe as a journalist and returned home seeking comfort in the familiar to raise her newborn son. But when former Wall Street Journal reporter Asra Nomani tried to pray in the main hall of Morgantown, West Virginia's new mosque, she was forcefully told she couldn't.

She grew up in the college town, traveled the globe as a journalist and returned home seeking comfort in the familiar to raise her newborn son. But when former Wall Street Journal reporter Asra Nomani tried to pray in the main hall of Morgantown, West Virginia's new mosque, she was forcefully told she couldn't.

Women had a separate prayer section. They also had their own entrance. Then she started hearing disturbing messages being preached during prayer services.

"The West is on a dark path."

"To love the Prophet is to hate those who hate him."

Had this happened at a different point in her life, Nomani may have reacted with indifference. But two seminal - yet overlapping - moments in her life prompted her to take a stand. The first was the kidnapping and murder in Pakistan of her friend and Wall Street Journal colleague Daniel Pearl. During the crisis that resulted, Nomani learned she was pregnant with her son. Her boyfriend broke up with her, leaving her a single mother.

"I was a criminal in the eyes of Islam and I knew I needed to bring my son into the world in a safe place," she explains.

In Pakistan, she was one of the last people to see Pearl alive. To Nomani, his murder represented the extreme end of the religious conservative spectrum. She decided to confront such thinking at home before it slid into insanity. She took on mosque leadership in a two-year campaign seeking acceptance of a reformist, more tolerant religious climate.

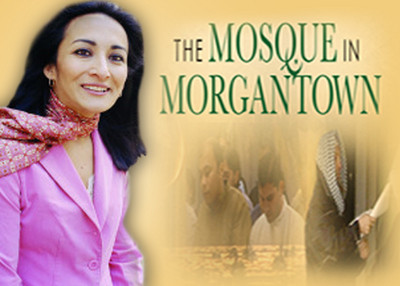

Her efforts attracted the attention of documentary producer Brittany Huckabee, who chronicled the largely-futile battle in "The Mosque in Morgantown," which premieres on PBS affiliates Monday, June 15 at 10 p.m. It is the final installment in the network's ongoing series "America at a Crossroads."

Early in the documentary, Nomani explains how Pearl's brutal slaying changed her outlook. As she spoke, she held pictures of Pearl taken just before he was killed:

"These are photos that were dropped off at a mosque in Karachi by the men who kidnapped Danny. They were Muslim militants who prayed five times a day and their reading of the Quran told them that they could do this. And these photos showed me the slippery slope of where intolerance and hatred can take us. And I wasn't going to accept it in my mosque in Morgantown. We had to have zero tolerance for the kinds of words that were spewing out of our pulpit. And I decided that I was gonna stand up even if I had to stand up alone. I wasn't going to just watch, as a journalist, and observe it. I was gonna protest. And that's when I became an activist."

Segregating men from women was one example of the conservative interpretation of Islam that Nomani believes is dominating American mosques. It is difficult to gauge how many others share her discomfort with mosque leaders who treat the Quran as the literal, unalterable word of God. Many of those who do are cowed into silence, she said, fearful of losing their friends or being outcast from their mosques.

That's what "The Mosque in Morgantown" shows happened to Nomani, her parents and a close friend who came to her side in the debate.

"It's a battle of ideas. It's a war of ideas," Nomani tells a radio interviewer early in the documentary. "Basically, this is about creating an inclusive and tolerant Islam in this world."

In an interview with IPT News, Nomani described Islam in America as "pre-Vatican II reform." Vatican II, initiated in 1962, sought a renewal of the Catholic faith, one that was more forward-looking and more tolerant of other faiths.

"We're at a place where a really hardcore interpretation of the faith prevails," Nomani said.

Despite the frustration chronicled in the documentary, Nomani has a decidedly optimistic attitude and uses humor to diffuse tension. She describes the program's confrontational scenes as "Jerry Springer elements." Required to cover her head inside the mosque, she took to wearing hooded sweatshirts.

"It's the 21st Century and I am courageous because I'm standing for my right to go into the mosque through the front door? It's so comical," she said.

And while it takes an emotional toll, Nomani finds inspiration from past American liberation movements. She talks of suffragettes who were jailed fighting to give women the right to vote. In the Civil Rights movement, peaceful protestors were attacked by police dogs and fire hoses.

Even when people claimed to agree with some of her goals, the documentary shows Nomani meeting with opposition for her direct approach.

During a 2005 book tour, she visited a Los Angeles mosque considered the nation's most progressive. Her attempt to participate in Friday prayers in the main hall is deemed unacceptably confrontational. First, officials cordon her off in a makeshift pen and recruit other women to pray with her.

Later, mosque leaders to challenge her integrity and motives.

"My advice: Islam before feminism," the late Hassan Hathout lectures her.

Edina Lekovic, a spokeswoman for the Muslim Public Affairs Council, tells Nomani that forcing the issue does more harm than good:

"Because of the means that we are adopting and because, unfortunately, many people understand your struggle as tied intricately to selling your book."

When Nomani told an older woman who had confronted her that she would pray for her, the woman snapped back:

"You don't need to pray for me. Don't you ever say that. I don't need your prayer. You are nobody."

(An extended video showing this confrontation, along with other excerpts from the documentary can be seen here. It is the last clip on the page.)

A "Jerry Springer element," to be sure, but to Nomani, the scene also illustrates a puritanical interpretation of Islam that builds walls between people with other views, of other faiths. That, she said, is the slippery slope that leads to conflict.

People at the Morgantown mosque could not see the connection or "even talk about it as an intellectual concept," Nomani said in the interview. They preach about other kinds of slippery slopes – that a woman wearing jeans could end up sliding down a path toward immodesty, or worse.

But the idea that they stood on the same side of the ideological spectrum as violent Muslim extremists was never considered. And Nomani was wrong to make such a challenge.

Salam al-Marayati, executive director of the Muslim Public Affairs Council, slammed the documentary after screening it.

"The show was not about that mosque but about Asra Nomani, a journalist. It was about Asra Nomani's quest for peace and justice among Muslims. After viewing it, I am left with the sense that Asra Nomani's quest is more within herself and not with her community. She needs to conclude what an American Muslim identity means for her."

Marayati seems to miss one point entirely, saying Nomani errs in pointing out Quranic verses which instruct Muslims not to befriend Christians and Jews and which sanction wife beating.

"Ms. Nomani points to certain translations of the Quran but fails to see that those translations are either inaccurate or incomplete in understanding the full context of what the verses are based on or what they are trying to promote."

The problem Nomani points out, however, is not the true meaning of the verses, but that she was hearing these messages preached from the pulpit.

Today, Nomani is an author and teaches journalism students at Georgetown University. She has led her students on the "Pearl Project," an investigation into the conspirators behind Daniel Pearl's murder and the reasons why he was targeted.

The Pearl Project is close to completion, Nomani said in the interview. When published next year, it will add new details about exactly who was involved. It is the continuation of a journalistic legacy that does not allow investigative reporting to be silenced, even by murder.

"I feel like we would have done what Danny would have done to stand up for fellow journalists," she said.

She plans to pursue a new project investigating the murder of other journalists abroad, perhaps one in Mexico.

Living near Washington, D.C., Nomani does not attend any mosque today. Her father checked out Northern Virginia mosques but could not find a comfortable fit. "There is no way I'm going to find anything but conflict with the ideologies preached from the pulpit," she said.

The rejection and isolation that resulted from her battles in the "war of ideas" has left Nomani unbowed, however. She's taking a break for now. "If you're constantly in confrontation and battle you're just going to have the life juices sucked out of you," she said. But she insists she's not ready to give up.

"The notion that the tolerant have to be tolerant of the intolerant is a nice philosophy. But in practice, you just end up being defeated by the hard core and they dominate. You can get denied your rights. I'm not ashamed of being intolerant of the intolerant."