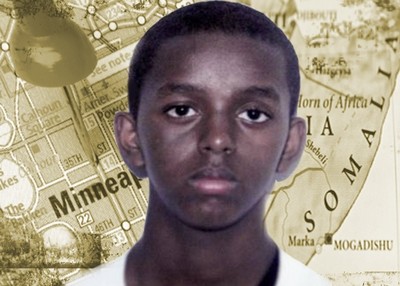

It was March 2009, and 17-year-old Burhan Hassan's family was very worried. Burhan vanished without a trace from his Minneapolis apartment on November 4, 2008. He had gone to his native country of Somalia - a country his family had left when he was just an infant - to join al-Shabaab's brutal war to overthrow the Somali government.

It was March 2009, and 17-year-old Burhan Hassan's family was very worried. Burhan vanished without a trace from his Minneapolis apartment on November 4, 2008. He had gone to his native country of Somalia - a country his family had left when he was just an infant - to join al-Shabaab's brutal war to overthrow the Somali government.

Burhan periodically called home to tell his family that he was "safe" and not to worry about him. But this call to his mother had a different tone. It had an urgent - even desperate – emotional quality that family members had not previously heard.

His message? That family members who had gone public with their concerns about him and the nearly 20 other Somalis who disappeared from the Minneapolis area since September 2007 could be putting his life in jeopardy.

Days earlier, his uncle Osman Ahmed had testified before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee about Burhan's disappearance. The March 11 hearing on al-Shabaab's U.S. recruitment efforts received international media coverage, Ahmed told the Investigative Project on Terrorism, and Burhan clearly was worried that the jihadist leaders were not happy with the attention he was receiving.

Burhan Hassan was killed less than three months later. On the afternoon of June 5, his mother received a call from someone claiming to be a member of al-Shabaab. Burhan had died that morning, the caller said. His mother flung the telephone against the wall.

The family last heard from Burhan less than two weeks earlier. He had difficulty talking, and had been battling malaria and another untreated illness. Relatives are convinced that al-Shabaab killed him to send a message to recruits who attempt to leave the organization and come home: Try to get out and you are signing your death warrant.

Hasan and the other young Somalis from Minneapolis were enticed to go to Somalia with visions of Islamic paradise. But the reality they discovered there – after it was too late to turn back – was a violent hell.

At least six of them have been killed - a traumatizing irony for their parents and other family members, many of whom fled that nation to escape its violence .

Adding to their anxiety is a concern among a growing number of Minneapolis Somalis that some Muslim individuals and groups have been countering the families' efforts to work with government agencies to bring home their children. First, the families accuse people tied to two local mosques of being complicit in radicalizing Somali boys and young men. Additionally, charge the relatives, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) has been discouraging Somali families from cooperating with law enforcement in an effort to find their missing children. Further, they say mosque leaders have been trying to discourage them from speaking out – claiming that if they talk to the FBI, their children could be sent to a detention facility like Guantanamo Bay.

A Bright Future

It would be difficult to imagine a less likely candidate for jihad than Burhan, Ahmed said in an interview. He was a "quiet, shy" child who obeyed his mother. He earned A's at Roosevelt High School in Minneapolis and took calculus and advanced chemistry courses. He talked of becoming a doctor or lawyer.

"Two months before he disappeared, he was planning to apply to Harvard," said Ahmed, who also serves as president of the tenants association at Riverside Plaza, a low-income housing complex in Minneapolis that is home to many Somali-Americans.

But then came the November day when he didn't come home after school. When his mother searched his room, she found Burhan's clothes and laptop were gone. So was his passport.

Family members also found receipts confirming the purchase of $2,000 in airfare to Somalia. Burhan had no job and could not possibly have earned the money to pay for the ticket himself, Ahmed said.

The ticket came from a local travel agency. An adult traveling with Burhan had purchased tickets for him and several other youths, representing himself falsely as a relative, Ahmed later learned. He was actually a jihadist recruiter, the family believes.

Three days after he went missing, Burhan called home to say he was safe. But he hung up when relatives tried to get more information.

Ahmed told the Senate panel that he is convinced his nephew and other youths who went to Somalia "had no clue they were being recruited to join al-Shabaab." Relatives have also learned that when the youths arrive in Somalia, "they are immediately shocked at what 'utopia' is and all their documents and belongings are confiscated. They are whisked to hidden military camps [for training.] They are also told that if they flee and return home that they 'will end up in Guantanamo Bay.' They don't know anything in Somalia."

The family began to sense that Burhan was having second thoughts, and by May or early June, he had agreed to return to the United States, Ahmed said. The family made contact with a relative in Nairobi who agreed to take Burhan to the U.S. embassy there. Shortly before he was killed, Burhan told his mother not to tell anyone he was coming home for fear that it would endanger him.

Ahmed said he has been told two contradictory stories about Burhan's violent death. In one, "a friend said he was walking around outside his home in Mogadishu" when he was "struck by a random bullet," Ahmed said. "Another story is that he was shot execution-style and hit in the face while in his bed in his home."

Burhan's family believes he was executed. "Al Shabaab killed him to silence him," Ahmed told the IPT. "They realized that he was traveling back to the United States with valuable information on al-Shabaab's recruiting in the United States" - including more concrete information on how many Americans had gone to Somalia to fight. Had he made it back to the U.S. to tell his story, "it would have been a terrible blow to al-Shabaab...He would have told how unhappy he was," Ahmed added. The family believes that al-Shabaab could not tolerate such an outcome and therefore killed Burhan Hassan to keep him quiet.

Muslims Target CAIR , Demand Answers from Two Twin Cities Mosques

A growing number of the estimated 40,000 Somali Muslims in the Minneapolis-St. Paul have expressed frustration with CAIR and two area mosques they believe are undermining the efforts of law enforcement to investigate the youths' disappearances.

Shortly after Burhan Hassan was killed in June, dozens of people in Minneapolis protested outside a CAIR ice-cream social against the organization's efforts to discourage Somalis from cooperating with the FBI.

"We don't want anyone to come into our community and tell us to shut up," said Abdirizak Bihi, another uncle of the slain teenager, at the protest.. "Law enforcement will not be able to do anything without information from the community."

The Minneapolis Star-Tribune reported that approximately 50 people attended the rally, waving signs and hollering, "CAIR Out, Doublespeak Out." The family again protested CAIR's actions on July 4, 2009. During that protest, flyers were handed out containing a powerful condemnation of CAIR's behavior:

"CAIR's provocative and dangerous actions will not be tolerated and have led many in the Somali American community to believe that they are intentionally shielding from prosecution members of a network which has been providing material support to a terrorist group, in this case funds and the trafficking of American youths to Al-Shabaab."

CAIR launched a campaign to make Muslims in Minnesota wary of religious profiling and the group has urged people approached by the FBI in Minnesota not to meet with agents without a lawyer. Jessica Zikri, CAIR-Minnesota's communications director, told the Star-Tribune that the campaign is meant to "ensure that civil rights are protected."

CAIR's Washington state affiliate is also working to discourage Somalis from cooperating with an FBI investigation of al-Shabaab recruiting in the Seattle area. Seattle Weekly reported last month that Arsalan Bukhari, executive director of CAIR's Washington state branch, was urging Muslims not to cooperate with police or the FBI.

"There's nothing to gain from talking to law enforcement," Bukhari told Somalis gathered at a local mosque. "There are too many things happening to Muslims recently."

"I can't emphasize enough," he repeated, "you have the right to remain silent, so please practice it."

To Osman Ahmed, CAIR's duplicitous behavior comes as no surprise. He maintains that CAIR is more interested in prying money out of the Somali community than in addressing its serious concerns about the jihadist recruitment.

Ahmed suspects his nephew was radicalized at the Abubakar mosque, which he had attended for 10 years. Similarly, several of the other missing young men had attended Abubakar As-Saddique Islamic Center, among them Shirwa Ahmed, who blew himself up in an October 29, 2008 suicide bombing carried out by al-Shabaab.

In a February 2009 speech, FBI Director Robert Mueller said Ahmed had apparently been indoctrinated in his extremist beliefs while in Minneapolis. While Mueller did not specifically mention the Abubakar mosque in his remarks, representatives of the facility reacted by denying that the mosque had anything to do with the youths' radicalization and suggesting the FBI Director did not know what he was talking about.

Neither the Abubakar mosque nor the Dawah Institute in St. Paul has provided much information about the missing youths, according to Osman Ahmed, who said they have tried to "silence" relatives who go public with their concerns about mosque radicalization. But Ahmed refuses to keep silent because he believes it is essential to speak out against the jihadist recruiters who prey on young people like his nephew.

When he attended prayers at the Islamic Dawah Institute in late 2007 and 2008, Ahmed said that on two occasions he witnessed Imam Hassan Mohamud calling on congregants to support "mujahideen." On one of those occasions, he saw the imam collecting money for them. Everyone there understood that "mujahideen" was a euphemism for al-Shabaab, Ahmed said.

Mohamud and the mosque deny they have supported al-Shabaab and insist that they oppose radicalism and violence. But Mohamud is clearly no stranger to inflammatory statements. The imam, who is an attorney who also has served as director of the Institute of Law at the local chapter of the Muslim American Society, defended the legitimacy of suicide bombings in a 2007 interview with Minnesota Law &Politics magazine:

"There are scholars who say that there is one place where suicide is not prohibited," Mohamud said. "It's an exceptional case for them because they have no other means. It is Palestine. This is because it is the only means they have to free their country."

In a fundraising video posted on YouTube last year (and since removed) Mohamud encouraged viewers to donate to a project sponsored by his mosque by telling them the mosque could save them from "the hell of living in America." Watch Mohamud try to defend his comments in a television interview here and consult with his attorney when asked if he is opposed to suicide bombings in all conditions.