Imagine the reaction if a newspaper hired a former National Rifle Association employee to cover a gun control referendum. Or if a former Goldman Sachs trader was offered by a television network as an objective journalist on financial reform.

Imagine the reaction if a newspaper hired a former National Rifle Association employee to cover a gun control referendum. Or if a former Goldman Sachs trader was offered by a television network as an objective journalist on financial reform.

Even those who agreed with the journalist's point of view would have to acknowledge the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Something similar may be happening when it comes to the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), a group federal law enforcement views with suspicion at best. In three separate instances in less than a month, reporters working for national news organizations have written stories compatible with CAIR's agenda without acknowledging their personal histories with the group. In two of the three cases, the reporter had been a full-fledged CAIR employee. In the third, the reporter had received a CAIR scholarship while a student.

Whether the cases are a matter of coincidence, they fit with an ambition outlined by CAIR co-founder and executive director Nihad Awad. During the 2005 Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) conference, Awad described the significance of getting more Muslims into mainstream journalism jobs (Hear it here):

"Second, to fix our image in the media over the next ten years, and to turn it, we have to invest in journalism. Today we have about between 50, in my estimate, and 100 Muslim journalists nationwide. In the next ten years, we have to encourage young Muslims to pursue the field of journalism and film making. And every major center in the country has to give a scholarship for one student. Ten years from now we will have 1,000 Muslim journalists and filmmakers. And this will be trusted in shaping the right image about the Muslim community, Muslim Americans and Islam."

News organizations rightly value a diversity in hiring, believing that newsrooms should reflect the communities they cover. Muslim reporters are a part of that diversity. But conflicts of interest remain a legitimate concern, too. If a journalist previously benefited financially from an organization, should he or she cover stories related to it?

In the three recent examples, the news outlet either didn't know about the connection or didn't find it significant enough to re-assign the story or disclose the connection.

1. Sharaf Mowjood was a government relations manager at CAIR's Los Angeles chapter before getting work with ABC News. Among his assignments with ABC, Mowjood co-authored a story on the FBI shooting of a Detroit imam as agents moved in to arrest him. CAIR, which has been ginning up allegations about the shooting for months, obtained autopsy photos and released some to the media. The ABC story quoted CAIR-Michigan executive director Dawud Walid rebutting FBI claims that Abdullah was dangerous. According to a criminal complaint, Abdullah preached violent jihad and vowed not to be taken peacefully if police ever came for him.

Four co-defendants with Abdullah were arrested without injury after complying with agents' orders to surrender. Abdullah fired his weapon first, FBI officials say, drawing return fire. The same day the ABC story came out, Detroit News reported Abdullah had a previous, violent encounter with a police officer following a 1980 traffic stop.

2. The Global Muslim Brotherhood Daily Report (GMBDR) website reported that the Associated Press assigned former CAIR-Canada spokeswoman Hadeel Al-Shalchi to cover a labor dispute at the Qatari-based website Islamonline. The GMBDR website described Islamonline as "the most prominent voice of the global Muslim Brotherhood," but said Al-Shalchi's story cast the Brotherhood as moderate and Brotherhood spiritual leader and Islamonline founder Youssef al-Qaradawi as a "relative moderate." The Brotherhood's ideology envisions the spread of Islamic law throughout the world. Qaradawi has issued fatwas sanctioning attacks against U.S. troops in Iraq and against Israeli civilians. In 2009, he said Hitler punished Jews "for their corruption" and predicted the next time it happened would be "at the hands of the believers."

3. In the most recent example, Los Angeles Times reporter Raja Abdulrahim included CAIR in a story about the fine line Muslim organizations walk in taking on extremism without "pandering to outsiders who equate Muslims with extremism."

Abdulrahim's college education was helped by a $5,000 CAIR scholarship awarded in 2003, a CAIR-California newsletter shows. As a student, she wrote several guest columns and letters to the student newspaper that were harshly critical of Israel or of U.S. policy after 9/11. In one, Abdulrahim rebutted another student who had been critical of terrorist groups. She felt the student:

"erroneously refers to Hamas and Hizbollah as 'fundamentalist' and 'terror organizations' that have 'murdered innocent Israeli civilians.' It is time we see this conflict for what it really is — present day Imperialism. These Palestinians are not 'terrorizing' Israelis, they are just defending their land and lives."

Such sentiments are well in line with CAIR's ideology. In the 2006 war between Israel and Hizballah, and the 2008-09 Gaza war with Hamas, CAIR ignored terrorist rocket fire on Israeli cities but demanded that the U.S. stop Israeli responses. While it claims to oppose violence against civilians, CAIR officials routinely dodge challenges to condemn terrorist groups like Hamas and Hizballah by name.

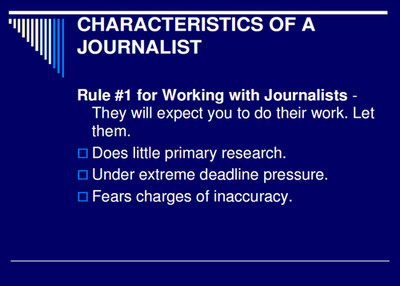

Like other Washington-based political groups, CAIR places great emphasis on media relations. It offers guidelines for letter-writing campaigns to local newspapers, coaching sessions for its chapter officials, and sessions at conferences devoted to getting its message out. Here's an assessment of a typical reporter from a PowerPoint presentation prepared by CAIR spokesman Ibrahim Hooper:

On this, CAIR seems to be onto something. Its officials routinely are quoted in daily newspapers and on television about grievances it has, or about issues related to American Muslims. But those news outlets rarely, if ever, inform their audiences of CAIR's questionable history in a Hamas-support network. Those roots are well documented in court records available on the Internet and in the assessment of high ranking federal officials. Perhaps, due to "extreme deadline pressure," reporters don't mind being spoon-fed the message and even the sources to tell their stories.

Federal prosecutors cast CAIR as "a participant in an ongoing and ultimately unlawful conspiracy to support a designated terrorist organization, a conspiracy from which CAIR never withdrew." A year ago, an FBI congressional liaison wrote that the Bureau would not engage in routine communication with CAIR "until we can resolve whether there continues to be a connection between CAIR or its executives and HAMAS."

CAIR appears to be the target of a federal grand jury in Washington, D.C., but that has not been widely reported.

We emphasize these statements from federal law enforcement officials because of their sources and because CAIR never really has addressed the evidence that generated them. That includes the presence of two CAIR founders on a telephone list for a U.S-based Hamas-support network and the inclusion of CAIR among the network's arms.

Plenty of people may look at the same documents linking CAIR to Hamas support and not see an issue. Fine. But they can't reach that conclusion if their news outlets never inform them.

Perhaps that has to do with the third point in the graphic above. In addition to fearing charges of inaccuracy, reporters abhor accusations of bias. CAIR, in perpetuating its claim as the voice of all Muslim Americans, has a history of labeling critics of the organization as "Islamophobes."

Ultimately, journalism is supposed to be an exercise in pursuit of the truth, of skepticism that challenges people to back up their claims and defend their statements and actions. CAIR already enjoys sympathetic media coverage. Stacking the deck with reporters tied to the organization makes it much more difficult for CAIR to be held to the same standard as other political organizations.

But then again, isn't that the point?