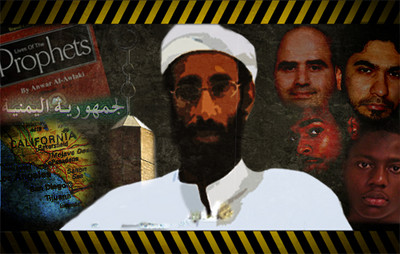

While the name Anwar al-Awlaki has become synonymous with terrorism, his path to the top of al Qaida's leadership can be traced back to his time as an imam in the United States. Linked to three of the most recent terrorist plots in the United States—the Fort Hood massacre, the Christmas Day bomb plot, and the failed Times Square attack—Awlaki first demonstrated a concerning radicalism over a decade ago.

While the name Anwar al-Awlaki has become synonymous with terrorism, his path to the top of al Qaida's leadership can be traced back to his time as an imam in the United States. Linked to three of the most recent terrorist plots in the United States—the Fort Hood massacre, the Christmas Day bomb plot, and the failed Times Square attack—Awlaki first demonstrated a concerning radicalism over a decade ago.

Awlaki shot into notoriety last fall, when it was discovered that he served as Hasan's confidante and inspiration in the lead up to a shooting spree at Fort Hood that killed 13 people and wounded 30 others. Since then, as each new plot unfolds, it seems like only a matter of time before a connection is made to Awlaki. As the U.S. government recently explained in designating Awlaki a terrorist:

"He has involved himself in every aspect of the supply chain of terrorism – fundraising for terrorist groups, recruiting and training operatives, and planning and ordering attacks on innocents."

More than anything else, Awlaki has become what the New York Police Department calls a "spiritual sanctioner." Providing religious justification for acts of terror, and with an American accent no-less, Awlaki's sermons calling for jihad continue to resonate among extremists seeking to fight the West.

But suggesting, as some have, that his current rhetoric is a substantial divergence from his prior position as a moderate is disingenuous.

The Investigative Project on Terrorism obtained several collections of Awlaki lectures on nearly 60 CDs in April at Halalco, a bookstore/market in suburban Virginia. CBN reporter Erick Stakelbeck first reported on the availability of Alwaki speeches and other radical material in June, prompting calls for the sales to stop.

The decade-old CDs were recorded in the late 1990s when Awlaki was the highly respected leader of the Masjid Ar-Ribat al-Islami, a Sunni mosque in San Diego. Among the themes of Awlaki's speeches were the evil that surrounds Muslims in the West; arguments that U.S. foreign and domestic policy are controlled by "the strong Jewish lobbyists;" and most commonly, his disdain of Jews, whom he terms "the enemy from Day 1 to the Day of Judgment."

Those who knew him when he lived in the United States argue that his calls for jihad against Americans simply don't track with the man they knew. His defenders maintain that his extremism is something that developed after he left the U.S. in 2002, driven over the edge by intensifying post-9/11 "War on Terror," and hardened into a full-fledged jihadist during 18 months in a Yemeni prison in 2006 and 2007.

He was portrayed as someone who could "build bridges between Islam and the West," and a voice for moderation, in a story on National Public Radio's "Morning Edition."

"It is the radical voices that are taking over, the ones who are willing to enter into an armed confrontation with their governments," Awlaki tells the reporter. "So, basically, what we have now is that all of the moderate voices are silenced in the Muslim world."

Similarly, San Diego immigration attorney Randall Hamud, who represented several Middle Eastern men who were arrested as material witnesses in the investigation of the Sept. 11 attacks, told San Diego Union-Tribune in January that there had been no hint that the imam had been hiding any extremist views from San Diego's Islamic community during his time there:

"The word I had at the time was there was no suggestion of radicalism by him….He was always portrayed as a moderate, and he left in high esteem."

Demonstrative of the esteem Awlaki enjoyed is a brief snippet from a 2002 PBS documentary, "Muhammad: Legacy of a Prophet," that shows Awlaki leading a prayer service sometime during the previous year for congressional staffers. Among those praying that day were Randall Royer, who later would plead guilty to a charge related to his part in a plot to train with the terrorist group Lashkar-e Tayyiba, and Nihad Awad, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

But treating these characterizations of moderation as anything but what they are—aberrations among a throng of evidence of radicalism—would be inappropriate.

A comprehensive review of Awlaki's sermons and speeches—some of which remain on sale at bookstores in the United States, show radicalism has been part and parcel of Awlaki's appeal from the beginning.

Among the concrete examples of the radicalism that Awlaki demonstrated over nearly a decade preaching in the United States:

In "Lives of the Prophets," Awlaki specifically prays to Allah to "free" the al Aqsa mosque, the third holiest site of Islam, from what he terms "the Jewish terrorists" who he claims "have taken (it) over" and "give it back to the Ummah of Islam." He goes on to make a clear call for the broad institution of Sharia law as the basis for society. "Justice is in the heart of the judge," he declares, "and that is why we can only have justice through true Islamic system."

"Here in America you have a corrupt law, but sometimes you have a good judge. Sometimes you don't. The combination that we want is the good law and the good judge. And that can only happen when the law is Islamic, and the heart of the judge is Islamic. But if the heart of the judge is not Islamic, no matter how good the law is, if it is Quran sitting on his desk, it wouldn't do anything. If the heart of the judge is not in line with the law, it won't do anything. " (click the play button to the right to hear the audio)

And Awlaki preaches patience and persistence in pursuit of victory: "In general, today, we are very emotional. We are fired up fast," he says on one CD. "There could be a very hot Khutba of Jumaa [a key Muslim service], talking about jihad, for example. During that Khutba, everyone feels like he is Khalid bin Walid [a military commander who served Muhammad]. He is ready to go on the battlefield." But, he says, "The Salaa [prayer] is over a few moments. Just by the time you step your foot out of the masjid [mosque], you leave all of that emotions behind you and you are back to Dunya [the world] again. Very easily fired up, and very easily we cool down."(click the play button to the right to hear the audio)

He makes that point again in a call for sustained commitment to jihad: "Talking big is easy, but the sacrifice, and especially long-term sacrifice which jihad needs, that is difficult. Jihad is not only sacrifice, but it is a long term sacrifice. And that is where people fail. If you are asked to sacrifice in one time, you could be fired up by a speech, and then you would give out your money, for example, and you would sacrifice. That could happen. But when you're asked to sacrifice for a long period, then you're suffering hardship for a long time, that is what causes people to fail." (click the play button to the right to hear the audio)

Sacrifice, he said, could take many forms and people should be willing to do whatever is required: "It could be your life, your time, your money, your family, it could even be the Islamic family or brothers that you are with, it could be the scholars that you love. Anything is possible."

While his extreme views can be seen throughout the CDs quoted, Awlaki has become more direct and transparent in recent years. His criticism of American response to 9/11 was immediate and visceral. In March 2002, after law enforcement officials raided a network of Islamic businesses and charities suspected of financing terrorist groups, Awlaki exploded in rage:

"So this is not now a war on terrorism. We need to all be clear about this. This is a war against Muslims! It is a war against Muslims and Islam. Not only is it happening worldwide, but it's happening right here in America, that is claiming to be fighting this war for the sake of freedom while it is infringing on the freedom of its own citizens just because they're Muslim, for no other reason. And as Muslims, if we allow this to continue, if we do not stop it, it ain't gonna stop! It's not gonna stop."

Awlaki was an imam at the Dar al-Hijrah mosque in Falls Church, Va., by this time. His message, that America is at war with Islam and Muslims, is considered pivotal in radicalizing young Muslims and turning them to violence. He soon left the United States to take his message of hate abroad.

By the end of 2002, Awlaki was in England, telling followers that "Islam overrides any other loyalty" and preaching the glories of martyrdom:

"I hear amazing stories for example with the mujahideen before their shahadah, statements that they make or smiles on their faces ....So they have a very pleasant ending."

And this type of violent rhetoric is still repeating itself today. In a tape released just this past March, he urged U.S. Muslims to launch violent attacks against the country:

"To the Muslims in America, I have this to say: How can your conscience allow you to live in peaceful coexistence with a nation that is responsible for the tyranny and crimes committed against your own brothers and sisters?" he asked. He termed jihad against America "binding upon myself just as it is binding upon every other able Muslim."

Last week, a new recording emerged in which he predicted Yemen could become the next American battleground. American arrogance and foreign policy generate terrorists' ire, including his own, he said:

"I could not reconcile between living in the US and being a Muslim, and I eventually came to the conclusion that jihad against America is binding upon myself, just as it is binding on every other able Muslim."

As the IPT's extensive review of Awlaki's written and spoken word reveal, the man now serving as the voice for al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula has indeed undergone a transformation since his time in America. But it is not the case of a man going from moderate to radical, but of a man going from a radical orator to a top recruiter of blood-thirsty jihadists.