I've been overwhelmed by a sense of déjà vu since hearing that National Public Radio fired news analyst Juan Williams for comments he made about his anxiety when he sees Muslim travelers in airports.

I've been overwhelmed by a sense of déjà vu since hearing that National Public Radio fired news analyst Juan Williams for comments he made about his anxiety when he sees Muslim travelers in airports.

It has been well chronicled that Williams spoke only of a personal and emotional response, and was quick to say he didn't believe all Muslims are extremists and that he didn't want people's rights violated by reactions to such emotions.

But NPR showed him the door anyway.

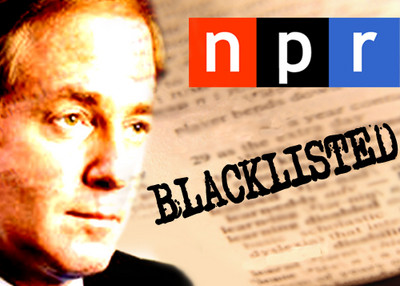

It's uncannily reminiscent of my experience getting blacklisted by NPR 12 years ago. I was interviewed by an NPR reporter in June of 1998 about a Hamas supporter named Mohammad Salah. Unbeknownst to me, a radical Palestinian activist and critic of mine wrote to NPR, expressing his horror that I was an NPR source. He did not take issue with what I said but asked if NPR didn't know what a bigot I was?

Ali Abunimah, then with the Arab American Action Network, a group that promoted radical Middle Eastern organizations and justified attacks on Israel, was told my appearance was a mistake that wouldn't happen again. But it did two months later, after al-Qaida suicide bombings struck American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. I was on NPR's "Talk of the Nation," which sent Abunimah over the edge. After only 20 minutes a previously scheduled 60-minute interview with NPR host Ray Suarez right after the US retaliated for the Kenyan and Tanzania attacks by Al Qaeda, Suarez suddenly yanked me from the show. I was suspicious about the fact that I had been specifically told that I would be on for the entire hour but had no idea whatsoever what was really going behind the scenes.

Boston Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby chronicled what happened next. (Kudos to Jacoby for picking up on the similarities between the Williams case and mine.) Abunimah fired off an email to a NPR network executive saying he had been told I wouldn't be on their air again. "Last time, I accepted the explanation that it had been an innocent error. But how many errors can be innocent? This is a very serious matter and will require an appropriate response," Abunimah wrote.

Producer Ellen Silva wrote back to apologize and say "you have my promise he won't be used again.

it is npr policy."

Call it what you want. I call it being blacklisted.

NPR Vice President Jeffrey Dvorkin denied this, however, saying "there is no blacklisting of anyone at National Public Radio. To accuse NPR of blacklisting is inflammatory." But the documents clearly showed that Dvorkin was lying.

I researched the matter further, compiling a report to memorialize the episode. You can read it here and judge for yourselves. And in this report, you can see all the internal NPR documents, the demands of Ali Abunimah that NPR acceded to, and the evidence showing an unambiguous pattern of NPR bias and dishonest reporting on radical Islamic groups.

Now, fast-forward back to Juan Williams. He made his comments on Fox News Monday. On Thursday, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) demanded that NPR "address the fact that one of its news analysts seems to believe that all airline passengers who are perceived to be Muslim can legitimately be viewed as security threats."

That's not what Williams said, but that didn't matter. NPR terminated his contract. Among the speculation is a belief that NPR had wanted Williams gone for some time and used this episode as a convenient excuse. Regardless if that's the case, or if the comments about Muslims alone sufficed, the incident shows nothing has changed at NPR since I was blacklisted.

If you stray from what is deemed acceptable political parlance, you're toast.

In my case, Abunimah invoked comments I made the day of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing – a truck bombing outside a heavily populated building. "This was done with the attempt to inflict as many casualties as possible. That is a Middle Eastern trait," I told CBS News. What Abunimah and other critics like him fail to recite is the rest of my answer: "That is a Middle Eastern trait and something that has been generally not carried out in this soil until we were rudely awakened to in 1993."

I specifically was referring to the 1993 World Trade Center attack, carried out with a fertilizer bomb in a Ryder Truck parked underneath one of the towers. Ironically, similar comments were made repeatedly in those initial 24 hours by NPR journalists. A sampling includes:

- "All Things Considered" host Robert Siegel on April 19, 1995, the day of the bombing: "The FBI believes the blast was caused by a huge car bomb containing more than 1,000 pounds of explosives. That's about the same size as the bomb that hit the World Trade Center in 1993." And, "The similarity to the World Trade Center bombing immediately makes one think of things Middle Eastern…"

- Reporter Mark Woodward the same show: "At this point, they've- they had- there's been word this afternoon, the local FBI agents gave a description of three men who they described as being of Middle Eastern descent driving a Brown pickup truck away from that area about the time of the explosion."

- "Morning Edition" host Bob Edwards on April 20, 1995: "Law enforcement officials are trying to determine what type of bomb caused the explosion. Some experts are comparing the blast to the World Trade Center bombing in 1992."

- Reporter John Nielsen on the same "Morning Edition": "Experts like Livingston say car bombs have become the favorite weapon of terrorists in recent years. A car bomb driven by a suicide driver blew up the U.S. Marine Corps barracks in Beirut in 1983. A bomb in a van destroyed part of the World Trade Center in New York in 1993. More than a hundred car bomb incidents have been reported around the world since the 1970s."

CAIR and others have used their selective use of my comment to try to discredit me and keep me off the airwaves ever since. It works with NPR. As Jacoby wrote at the time:

"CAIR's world view is simple: Criticism of anything linked to even the most fanatic wings of Islam is bigotry. (For example, it labeled a "hate crime" the arrest of Sheik Omar Abdul Rahman, ringleader of the World Trade Center bombing.) Its approach to press relations is also simple: Deluge media outlets with protests, invective, and cries of "racism!" when they publish or broadcast stories unflattering to Islamic extremists.

Because Emerson has shed so much light on the operations of these zealots, his appearance drives them into a particular froth. Right after his NPR interview, CAIR urged its adherents to go on the attack."

The evidence clearly shows that I was blacklisted. And while NPR had me on a few times after 9/11, I haven't been heard there since 2005 even though our organization operates one of the largest archival data bases in the world on radical Islamic activities and groups in the United States and their ties abroad. In fact, the last time I interviewed me for a story on NPR was in 2005 for a story on radical Islam, my comments never appeared in the story.

Since 2005, prosecutors won convictions in the country's largest terror financing case, one I had been writing about since 1995. That trial exposed secret connections between CAIR, its founders and the same Hamas-support network that was prosecuted.

Yet, since then NPR never sought my opinions or expertise on the matter. I wonder why.