Time and time again, the United States has set itself up for long-term failure in the interest of preserving short-term face. American forces fighting in Afghanistan have faced threats from training and munitions provided to the Afghan fighters in the 1980s that led to the Taliban's rise to power. In that instance, the United States chose to arm a rebel force in an effort to defeat a Soviet invasion of a country with limited strategic importance, in order to maintain its position in the "cause du jour" of stamping out communism wherever it may exist.

Time and time again, the United States has set itself up for long-term failure in the interest of preserving short-term face. American forces fighting in Afghanistan have faced threats from training and munitions provided to the Afghan fighters in the 1980s that led to the Taliban's rise to power. In that instance, the United States chose to arm a rebel force in an effort to defeat a Soviet invasion of a country with limited strategic importance, in order to maintain its position in the "cause du jour" of stamping out communism wherever it may exist.

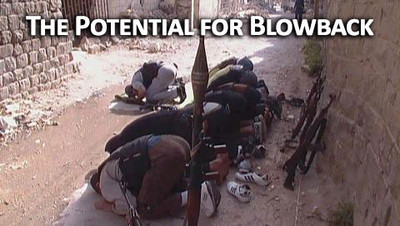

Today, though the cause has changed slightly, we find ourselves ready to jump headlong into supporting the underdog in a fight to establish "a just and democratic state" in Syria. Though the long-term negative ramifications of arming the Afghan Mujahedeen were not immediately apparent, the present-day question of dumping arms into the Syrian civil war could pose immediate negative results for the United States and its interests abroad.

U.S. Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., introduced the Syria Stabilization Act of 2013 last week, calling for sanctions against supporters of the al-Assad regime, humanitarian relief for refugees, and the arming of Syrian rebel forces. Menendez, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, said the steps were necessary amid indications Assad used chemical weapons and because "[t]he greatest humanitarian crisis is unfolding in and around Syria."

Assad's forces have killed 80,000 people and displaced nearly 3 million more during the two-year-old uprising. There is growing concern he might lose control of his chemical weapons stockpiles. Those weapons likely were used against Syrian civilians. Meanwhile, the "security vacuum" within Syria has provided an unobstructed operating environment for Shia and Sunni extremists who "could in the future threaten the security of the United States and its partners."

One group, Jhabat al-Nusra, is an immediate threat. The group, otherwise known as the Al-Nusra Front, is a primarily Sunni terrorist group with sworn allegiance to Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. A Quilliam Foundation report on Al-Nusra indicates the group's main objectives were decided during meetings in later 2011 and include:

1. "to establish a group including many existing jihadists, linking them together into one coherent entity,

2. To reinforce and strengthen the consciousness of the Islamist nature of the conflict,

3. To build military capacity for the group, seizing opportunities to collect weapons and train recruits, and to create safe havens by controlling physical places upon which to exercise their power,

4. To create an Islamist state in Syria, and

5. To establish a 'Caliphate' in Bilad al-Sham (the Levant)."

While Menendez's proposed legislation limits American support only to opposition forces which "have been properly vetted and share common values and interests with the United States" senior members of the somewhat more conventional Free Syrian Army (FSA) describe al-Nusra as "[t]he strongest military force in the area." Younger FSA members look to the group with reverence due to its efficiency and prowess in battle against the Syrian Army, while some even called the group "the special forces of Aleppo." From the FSA's perspective, al-Nusra is well-positioned to influence any successive government. Most assuredly, if al-Nusra has its way, such a government will be dominated by Shariah law and far from the democracy the United States and its allies hope to establish.

While a hardline Islamist state sharing a border with Israel is scary enough, the more frightening threat stems from al-Nusra's stated objective to secure additional weapons – both conventional and chemical – which will be readily available following Assad's fall. This situation presents a significant policy dilemma for an administration whose "red line" in the sand seems to obligate American forces to respond to prevent the (further) use or release of chemical weapons.

The White House is left with the unenviable task of deciding between several courses of action, including: limiting its response to caring for 2.5 million Syrian refugees while increasing support for neighboring countries; providing continued support to Israel in its defensive strikes on weapon systems leaving Syria; direct action by either surgical air strike or land-based invasion; or if Menendez has his way, providing $250 million per year in weapons and transition assistance to "vetted" opposition forces in the hope such support will not be one day turned against us.

Given the increasing connection between rebel forces and al-Qaeda-tied terrorists seeking a path of religious extremism, support of rebel forces is likely to cause long-term harm to the United States and its regional allies. In its desire to do something, the administration risks feeling the sting of a grand scale Middle East Operation "Fast and Furious" gone wrong if arms sent to rebels wind up in the hands of terrorists. After all, sometimes the enemy of my enemy…is still the enemy.

Frank Spano serves as the Director of National Security Policy for the Investigative Project on Terrorism.