DETROIT - Rasmieh Odeh's fate may turn on a parsing of the word "ever."

DETROIT - Rasmieh Odeh's fate may turn on a parsing of the word "ever."

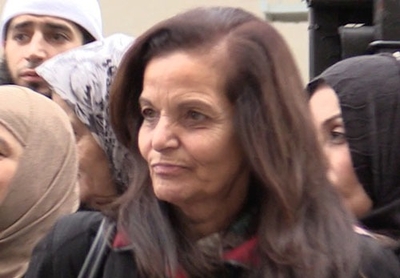

Odeh, 67, is on trial for one count of naturalization fraud. When she first applied to come to America in 1995, and when she applied in 2004 to become a citizen, Odeh checked "no" on immigration forms which asked if she ever had a criminal record.

In fact, she had been convicted by an Israeli court for a series of 1969 bombings in Jerusalem. One killed two college students inside a Supersol grocery store. The other damaged a British consulate building. Odeh was sentenced to life in prison but released in 1979 and sent to Lebanon as part of a prisoner exchange.

She moved to Jordan before coming to a Detroit suburb where her father and brother lived.

Those facts, federal prosecutor Mark Jebson said in opening statements Wednesday, make this "a simple and straight-forward case." To obtain permanent residency in America, better known as a "green card," applicants must disclose all the places they've lived as adults and show that they have no major criminal convictions.

Odeh "lied about her criminal record during the entire citizenship process," Jebson said. That includes in her application and in a subsequent interview, conducted under oath, with an immigration officer.

She "never should have been allowed into the United States," Jebson said.

But in his opening statement, defense attorney Michael Deutsch said Odeh thought that the questions asking if she ever had been arrested, convicted or jailed applied only to her life in America. The form does not specify whether someone was arrested in a foreign country, he said. Odeh never thought she was being asked about a conviction from 40 years earlier.

In Jebson's opening and in subsequent witness testimony, however, jurors saw the actual applications Odeh submitted. The word "ever" in reference to criminal histories is in bold font with capital letters. For applicants who might answer yes, they are asked to provide the city, state and country of the offense.

Jurors also saw a short video excerpt from a 2004 documentary showing Odeh describing life in prison. That documentary, prosecutors noted, came out the same year Odeh applied to become a citizen and denied having any criminal record.

The defense isn't contesting that Odeh was in the Israeli prison, Deutsch said. It does argue that her failure to disclose that fact on the immigration forms was not a lie and not a crime.

When U.S. District Judge Gershwin A. Drain said during jury selection on Tuesday that Odeh had been convicted in a bombing, he didn't say it was a ruling issued "by an Israeli military court that was occupying Palestinian land," Deutsch said in his opening statement.

"You're the only independent party here," he told jurors.

Drain admonished Deutsch in front of jurors a few minutes later. He hadn't mentioned the military court because Deutsch didn't ask him to, he said.

"I want you to be careful about what you say and how you say it," Drain said. "You kind of implied that I'm not being neutral here."

It wasn't the only time Drain told Deutsch to respect the court and its decisions.

Deutsch asked prosecution witness Stephen Webber, a special agent with Homeland Security Investigations who led the investigation into Odeh, whether he conducted "an independent investigation" into the fairness of Israeli military courts.

In pretrial rulings, Drain placed restrictions on both sides. Prosecutors and their witnesses are not allowed to describe Odeh as a terrorist or describe the bombings as a terrorist act. Israeli records proving her conviction took place have been heavily redacted.

Defense attorneys are barred from arguing that the Israeli conviction was based on torture Odeh claims to have endured, or that Israeli courts did not provide due process for Palestinians. Rather, the charge is whether Odeh knowingly lied on her applications and in interviews with immigration officials in order to become a citizen. Drain reinforced his ruling earlier Wednesday.

Deutsch pushed that line several times, including in his question to Webber, perhaps hoping to plant a seed among jurors to ignore the paperwork and acquit his client.

"Please abide by my rulings," Drain said.

Odeh's supporters waged a year-long public relations campaign aimed at getting the charges dropped. They packed the small courtroom Wednesday, with dozens more watching on a video feed in an overflow room.

Deutsch described Odeh as "a woman of character and dignity and honesty." In concluding his opening statement, Deutsch also argued that the current charge against Odeh is unjust. She was naturalized a decade ago, he noted. Why is she only being tried now?

Prosecution witnesses provided an indirect answer. In addition to denying she had a criminal record and had served time in prison, Odeh reported that she lived only in Amman, Jordan since she was 16. That overlooks the 10 years in an Israeli prison.

Had Odeh disclosed she lived in Israel, immigration officials might have checked with their Israeli counterparts to see if she had a criminal record. "It is difficult to verify a criminal record in other countries," said prosecution witness Raymond Clore, II, a career State Department official who ran the consular section in Amman, Jordan when Odeh applied for a visa in 1994.

It's especially difficult if the immigrant fails to list all the places she lived previously.

Certain details about an immigrant can be "stop signs" that would prevent them from getting into the country, Douglas Pierce, a section chief in the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services office in Detroit testified. Individuals are deemed inadmissible if they have a communicable disease or if they have been convicted of a serious crime.

Jaywalking, he said, wouldn't keep someone out. Being convicted in a bombing which killed two people would.

Deutsch portrayed Odeh as something far from a cold-blooded killer. She "embodies the modern history of the Palestinian people," he said, describing her life as filled with "great suffering and great resistance."

Deutsch told jurors that Odeh will take the stand and testify about her answers.

Pierce was still being questioned by the government when the trial recessed Wednesday. On Thursday, he is expected to explain how he trains all his immigration officers to make it clear during interviews with people applying to become American citizens, that the "ever" in questions about criminal histories applies to any place in the world.

Jennifer Williams, an immigration officer who works for Pierce and who conducted Rasmieh Odeh's interview before becoming a citizen, also is expected to testify and say she followed Pierce's direction on those questions.

The trial is expected to last through Friday. For more background on the case, see our five-part video series, "Spinning a Terrorist Into a Victim."