Afshin Ellian has a thing or two to say about terrorism.

Afshin Ellian has a thing or two to say about terrorism.

He also has a few things to say about Islam – specifically political Islam – but many don't particularly like to hear it. In fact, the threats against his life from radical Muslims, particularly in the Netherlands, where the Iranian dissident now lives, have become so frequent that at least one bodyguard accompanies him anywhere he goes.

But Ellian, a professor of jurisprudence at the University of Leiden, also knows a thing or two about freedom: he has spent his life pursuing it since his days as a student in Iran, where in 1978 he took part in the uprising against the Shah. After the revolution, the Ayatollah banned political discourse; threatened with execution, Ellian fled the country. He settled briefly in Kabul before further ideological conflicts led him to escape again, arriving as a political refugee in the Netherlands in 1989.

Now the human rights and counter-terrorism expert works valiantly to protect the freedom that he so long fought for – even as he finds the most precious quality of that freedom itself now under threat: the principle of free speech.

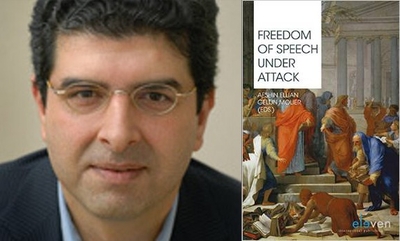

It is this which recently brought him to the Nieuwspoort, a debate center for journalists and politicians in The Hague, a city not coincidentally known as "the International City of Justice and of Peace." The occasion: the presentation of his latest book, simply and appropriately titled Freedom of Speech Under Attack.

In the post-Charlie Hebdo era, it is a book that defines our time.

Speaking to assembled press and his guest of honor, Flemming Rose – the publisher of Jyllands Posten and the renowned "Danish Mohammed cartoons" who also lives under guard – Ellian is clearly unbowed by the threats and attacks on his own freedom. To the contrary, he speaks the words many would prefer went entirely unsaid: Europe must defend itself against radical Islam. To do so, its strongest weapon, stronger than arms, stronger than money, is the protection of free speech.

Yet at the same time, the very principle of free speech is being abused by jihadists to destroy the democracies from which it was created, says Ellian. Recruiters for jihad, those who threaten apostates and Jews and who call for violence against the West rely precisely on the principles of free speech to spread their messages of hate. Consequently, he says, "democracy as a form of society must be understood in terms of a militant system. Whenever democracy is threatened by violence, it has the right to defend itself violently. The alternative would be suicide." And freedom, he pronounces, "is no suicide pact."

Ellian's own confrontation with radical Islam in Europe dates back to 2002, when an article he wrote against the Prophet Mohammed's orders to destroy poets led to death threats. (In addition to holding graduate degrees in philosophy and law, Ellian is a celebrated poet.) More threats followed, chiefly after the murder of Theo van Gogh in November 2004 by Muslim extremist Mohammed Bouyeri. Immediately after the killing, Ellian called on other Western intellectuals to "put radical Islam on the surgical table" and to fight back against politically correct censorship because, as he says now, "whenever a society applies self-censorship out of fear from terrorism, freedom dissipates.

Yet days after the presentation of Ellian's new book, six members of PEN America, the prestigious organization for authors and writers that defines itself as a leader in the defense of free expression, called for a boycott against the association, citing its decision to honor the magazine Charlie Hebdo with its Toni and James C. Goodale Freedom of Expression Courage award. When I tell him of this, Ellian's fury sizzles through the phone.

"If you start with saying they shouldn't make the cartoons," he fumes, "you may as well say they shouldn't write novels. After all, what have the Jews done? Why are they killed? Would the writers say they shouldn't have been Jews? A writer who cannot tolerate such a prize is not worthy of the name 'writer.'"

Indeed, it is precisely in the fight against terrorism, says Ellian, that the debate over free speech becomes most crucial – and where writers and intellectuals should speak out the most loudly.

"We in the West have the possibility of discussion," he says, "the ability to talk about morals and religion. We can't take on the model of the Islamic world. To the contrary: they need more freedom. We don't need less."

After all, it is just that inherent intolerance for debate that led to the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo, the threats against people like Salman Rushdie and Flemming Rose and Ayaan Hirsi Ali (who, not coincidentally, studied under Ellian in Leiden) – and, of course, against Ellian himself.

That's not to say that free speech has no limits, Ellian cautions, and this is what his book sets out precisely to address: what are the limits on expression and on speech, not only for philosophers and novelists, but also for jihadists? What can they say? What can they not say? Should speech that encourages hate and discrimination be criminalized? What about blasphemy? And what of the spread, particularly on the Internet, of anti-Semitism, and efforts to recruit others for jihad?

"For me," says Ellian, "the limit comes at the point of calling for violence. But not like in France, where they have criminalized 'glorification of terror.' In my opinion, that goes too far." He recently filed a civil complaint against Shabir Burhani, alias Maiwand Al Afghani, a former spokesperson for Sharia4Belgium, alleging threats and the promotion of violence. (Burhani, then a student at the University of Leiden, was also accused of threatening Ellian directly in 2013. He has denied the charges.)

In the end, it comes down to a simple, basic principle: that freedom cannot be used for the purpose of limiting freedom – a form, as Ellian suggests, of suicide. But in the face of political Islam and Islamic terrorism, it can neither be absolute. "This," he says, "is the core of terrorism. Terror wants to bring us back to 1,500 years ago. They want us to no longer write. But if you say, 'you can't talk about Islam,' if you tell us to hold our mouths still, then terrorism has won."

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands.