which even calling the Israelis "Nazis" in her Brief can't overcome.

Rasmieh (Rasmea) Odeh is the convicted bomber of the SuperSol supermarket in "West" Jerusalem in 1969 which killed Edward Joffe and Leon Kanner. The evidence of Rasmea's guilt was and is overwhelming, and has grown more so over the years.

See my prior posts on the case:

- Rasmea Odeh rightly convicted of Israeli supermarket bombing and U.S. immigration fraud

- Prosecution seeks 5-7 year sentence for Rasmea Odeh (included new evidence of guilt)

- Rasmea Odeh's victims – then and now

Rasmea had a lawyer in the Israeli trial, and engaged in extensive pre-trial litigation and trial that stretched over the better part of a year. An International Red Cross observer termed the trial to be fair.

While Rasmea would claim that the conviction was the result of her confession coerced through 25 days of sexual torture, in fact Rasmea confessed the day after arrest and there was evidence independent of the confession. Moreoever, years later, after they all were out of prison, Rasmea's main co-conspirator would credit Rasmea with being the mastermind.

Rasmea was sentence to life in prison, then was released in 1979 in a mass prisoner exchange for an Israeli soldier captured in Lebanon. She eventually made her way to the U.S. in the 1990s

In November 2014, Rasmea was convicted in federal court in Detroit of lying on her immigration and naturalization forms, by falsely denying she ever had been arrested, convicted or imprisoned. Rasmea was sentenced to 18 months in prison and ordered deported. She is free on bond pending appeal.

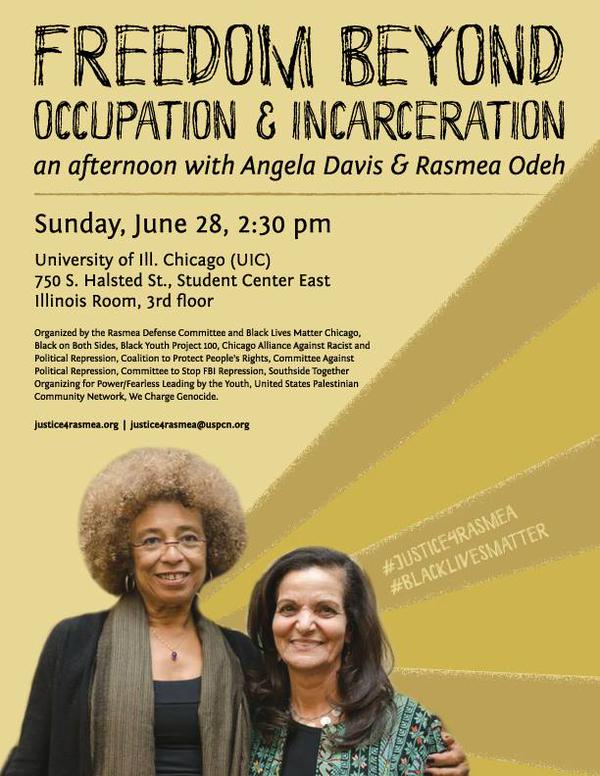

Rasmea is being treated as a hero of the anti-Israel community in the U.S., with live stream fundraisers and celebrations.

She also has latched onto the Black Lives Matter movement to help generate support for her. Here she is with her lead attorney, Michael Deutsch:

Rasmea's appeal brief was filed on June 9. (Full copy embedded at bottom of post.)

The Brief alleges three main grounds for appeal: (1) the Court deprived her of her right to present a full defense by refusing to allow her to testify that the Israeli conviction was obtained through torture and to call an expert to testify that PTSD caused her to block out the Israeli conviction and prison time when interpreting the term "EVER" on the questionnaires; (2) the Court allowed in unduly prejudicial Israeli military court documents which disclosed the bombing conviction and the names of the two people Rasmea killed; and (3) the prison sentence was unjust.

Mixed in with these legal arguments is the type of noxious rhetoric we have come to expect from Rasmea's attorneys and supporters. In the Brief they compare the Israeli military tribunal — which even the Red Cross said gave Rasmea a fair trial — to "a Nazi court operating in occupied France that convicted partisans resisting occupation." (Brief, at 36)

I don't predict how courts will rule, particularly not appeals courts. There are some issues that are legitimate appeals issues, though weak, such as the claim that revealing the nature of Rasmea's Israeli conviction and the names of Rasmea's victims was unduly prejudicial; and that the court applied the wrong standard of intent for the crime. I'm not expecting her to win on those, but at least they are the types of issues one would expect to be raised on appeal.

But there is a fundamental inconsistency in the appeal that should taint, if not completely eviscerate, Rasmea's legal arguments. Rasmea's appeal takes the legally and factually inconsistent positions that Rasmea had an actual, conscious understanding of the word "EVER" that limited the time scope to her time in the United States in the context of other questions on the form; and separately, that PTSD from the alleged torture caused her to block out the Israeli conviction and imprisonment.

Here is an excerpt from the Brief (at p. 7) on the issue of the word "EVER":

Ms. Odeh did not contest that she had been arrested, convicted and imprisoned by the Israeli military in 1969, at trial or otherwise. Rather she testified that she believed at the time that the naturalization questions, coming more than nine years after she began living in the U.S., referred only to her time in the in the United States — where she had no criminal record — and that she never thought about her time in Israel in providing her "No" answers on her form or in the interview. R.E, 182, pp. 116-120, Pg. ID 2364-2368. She also stated that a series of prior questions on the naturalization application which used the words "Ever" and referred to the United States, reinforced her understanding that the later questions,about prior arrests convictions and imprisonment, also referred to the United States, See Exhibit lA, R.E. 186-1 pp. 6-7, Pg. ID 2620-21; (Testimony of Rasmieh Odeh), R.E. 183 pp. 53-54; Pg. ID 2426-27.

She explained that she would not have hesitated to disclose her Israeli conviction and imprisonment if specifically asked, since it was no secret. R.E. 182, p. 120, Pg. ID 2368; R.E. 183 p.21; Pg. ID 2394. The evidence also showed that she had told a Homeland Security Agent in 2013, that no one from Immigration ever asked her about her Israeli imprisonment at the time of her naturalization process. R.E. 183, pp. 18-21, Pg. ID 2391-2394; Testimony of Stephen Webber) R.E. 181 p.91, Pg. ID 2181.

[Note: The trial transcript is not yet publicly available, so I cannot quote from the transcript or verify the page references in the Brief.]

Got that? Rasmea had a conscious understanding of the form based on the wording and sequence of questions, and would not have hesitated to disclose the conviction and imprisonment if she thought it was called for by the questions.

But, the second part of the explanation says the opposite, that her PTSD caused her to block all those things out:

Dr. Fabri [the proposed expert] testified, in a Rule 104 hearing, that after extensive interviews and testing, she diagnosed Ms. Odeh as suffering from a chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) resulting from torture. Dr. Fabri opined that the disorder could have operated to automatically "filter out" her terrible traumatic experiences in Israel, and cause her to interpret the naturalization questions as way to avoid any thought of her past trauma. (Testimony of Dr. Mary Fabri), R.E. 113, pp 11-16, 38-45, Pg. ID 1165-1170, 1192-1199.

Initially, the lower court ruled that the statute, 18 U. S. C. § 1425, charged a specific intent crime, and ordered the 104 hearing to "ascertain whether Defendant's expert's anticipated testimony 'will support a legally acceptable theory of mens rea. "'(Order and Ruling of District Court). R.E. 98 pp; 7-15, Pg. ID 982-990. Prior to ruling on the admissibility of Dr. Fabri' testimony however, the comi reversed his position in response to a government motion for reconsideration, and held that the statute charged a general intent crime, and consequently, as a matter of law, Dr. Fabri could not be permitted to testify. (Order and Ruling of District Court), R.E. 119, pp 1-7 Pg. ID 1252-1258.

So which was it? Rasmea was conscious of the conviction and imprisonment but didn't think the questions called for disclosure, or she blocked everything out because of PTSD arising from alleged torture more than 25 years earlier? You can't have it both ways, but Rasmea's appeal tries to.

This has profound implications for the legal aspects of Rasmea's appeal. Her own trial testimony negates the claimed need for an expert witness, even assuming there were a legal basis for the expert; Rasmea would have been calling the expert to contradict Rasmea's own trial testimony. This would render any legal error as to the expert "harmless" and not the basis to overturn the conviction.

There are many other problems with the appeal, such as the claim that it was improper to admit documents from the Israeli military court because such documents were just like Nazi courts according to Rasmea's attorneys. But the documents were admitted to prove the fact of conviction and imprisonment, which were undisputed.

Also, there was no need to allow Rasmea to contest the underlying Israeli conviction — the immigration questionnaires did not ask whether she was rightly or justly convicted and imprisoned, only whether she had been convicted or imprisoned. As a factual matter Rasmea was convicted and imprisoned, and needed to disclose it.

In all, the appeals court of necessity must take account of the fundamental inconsistency in Rasmea's appeal which goes to the heart of her appeal claims as to excluding the supposed expert witness and PTSD evidence.

A legal group that supports anti-Israel BDS and other activists, the Center for Constitutional Rights, has filed a request to file an Amicus Brief supporting the need for expert testimony on PTSD. That Brief, which appears to be generic and almost devoid of context in this case, is irrelevant for the same reasons — the PTSD evidence would contradict Rasmea's own trial testimony that she would not have hesitated to reveal the conviction and imprisonment if she thought the questions asked for it.

The government's brief is due in early July, Rasmea gets a reply by the end of July. If oral argument is granted, that likely will be in September.