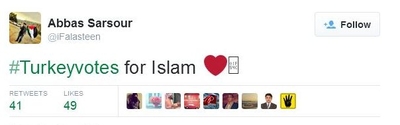

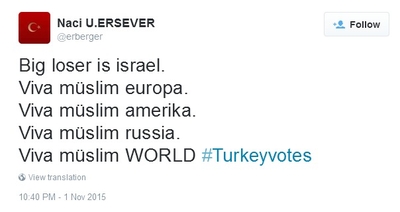

The shouts ricocheted across cyberspace, on Twitter and Facebook, in e-mails and messages and banners: "Turkey votes for Islam!" "Islam wins! America loses!"

The shouts ricocheted across cyberspace, on Twitter and Facebook, in e-mails and messages and banners: "Turkey votes for Islam!" "Islam wins! America loses!"

And so the Muslim world greeted the news on Nov. 1, that Turkey's ruling party, the Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP), won an unexpected landslide victory in the country's snap elections, commanding just over 49 percent of the vote.

And so the Muslim world greeted the news on Nov. 1, that Turkey's ruling party, the Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP), won an unexpected landslide victory in the country's snap elections, commanding just over 49 percent of the vote.

In the week since, conversations have focused on what this says of Turkey and the future of the region. The AKP, led by Turkey's autocratic President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, re-secured its single-party rule over the country, and with it, the power to impose its misogynistic, conservative, Islamic order on what remains of Ataturk's secular Turkish Republic.

But if this resurgence of Erdogan's party after a momentous loss in June came as a shock to the country's intellectual, secular elite, the real shock is not what took place in Turkey. It is rather what the elections revealed about Europe – or specifically, about its 4 million Turks and their descendants who also voted, as it were, for Islam.

To recap: The AKP suffered a major loss in June's parliamentary elections as the pro-Kurdish party, HDP, commanded enough votes to break the standing AKP majority and force a coalition government. But coalition talks crumbled, leading Erdogan to call a snap election for November. In the days leading up to the vote, pollsters predicted an outcome similar to June, and that a coalition was inevitable.

They made one grave mistake: ignoring the foreign vote.

Across Europe, Turkish immigrants voted massively for the AKP. In both Belgium and The Netherlands, a dizzying 70 percent of Turkish voters supported Erdogan's party, as did 68.8 percent in Austria. Close behind were Germany, with nearly 60 percent of the Turkish votes, and 56 percent in France. Put another way, more European Turks per capita supported the Islamist party than did voters in Turkey itself.

Why? And what does this say about Europe's Turkish population?

Turkish immigrants swarmed into Europe in the decades after World War II as guest workers, picking up manual labor Europeans were no longer willing to perform. They came mostly from rural areas. They were uneducated, often – especially the women – illiterate. They were deeply religious. Few learned the languages of their host countries, though they were not expected to. They were guests, after all, and would be leaving soon. And so they were ghettoized, shielded from the Western lifestyles and values that surrounded them.

They were, in essence, the same people who now provide the backbone of AKP support in their homeland.

In itself, that seems explanation enough, except that most of the 70 percent of Dutch Turks who voted AKP are second- and third-generation, born and raised in the West, presumably with the values of a Western, secular democracy. That information comes from a man Volkan, a co-founder of the Dutch Turkish Foundation (who requested his full name not be used for security reasons).

What to make of their support of a party led by men who believe, for instance, that women should not laugh in public; that men and women are not equal; and who support the building of a "new, religious generation" by forcing children to attend conservative, Islamist schools and religion classes?

Such issues have nothing to do with the AKP's popularity in the Netherlands, Volkan said, though he was also quick to excuse and explain away many of Erdogan's more anti-democratic remarks. "He didn't say women were unequal," he argued, "he said that they were different" – an interpretation apparently not shared by Turkish opposition leaders, who were outraged.

Equally insignificant for Dutch supporters of the AKP, apparently, were Erdogan's commitments to build "a new, religious generation," his resuscitation of Ottoman script – banned by Ataturk – or the arrest, under his own mandate, of children who defaced an AKP poster days before the election.

Instead, Volkan believes Turkish voters in Europe were swayed by the "Ten Promises" made to them by Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu. They include such outright bribes as 20 percent discounts for families of three or more (note the implied urging of childbearing) traveling to Turkey on Turkish Airlines; cash bonuses for newlyweds and newborns; a reduction in a fee that excuses them from compulsory military service and so on. Included in the list is a so-called "Youth Project Europe," for which no description has been given.

They voted for it anyway.

Interestingly, this is not all that different from the way the AKP operates at home – buying gifts for families, promising a future of riches and the blessings of Allah. In Turkey, the party base remains the uneducated, religious masses; and it is worth noting that even the second generation of European Turks is, by and large, less-well educated and more religious than other Europeans. Many suffer language challenges in grade school that hold them back. Some are hindered by their parents' inability to help with their studies, either because of language barriers or literacy problems. Parents can rarely afford to send them to the elite, higher-quality private schools. The drop-out rate is high. The cycle runs through generations.

Many find solace and meaning in the mosques. Others find purpose through the recruiters for radical Islam they meet there, recruiters who offer them dreams of Paradise and redemption – and sometimes money. And most, it seems, fall equally for politicians' promises and handouts.

Obviously, one prefers those who vote AKP to those who join al-Qaida and the Islamic State. Nonetheless, the massive number of supporters – a combined 1.5 million in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands alone – speaks volumes about the values of millions of European Muslims.

And it also speaks to how little European officials are doing about it. The AKP, for instance, specifically targeted Dutch and German Turkish immigrants, whose personal addresses they obtained via resources within their own government. Some of those methods violate European privacy laws and gave the party an enormous advantage over its rivals. Consequently, as Volkan notes, the AKP was the only party that actually reached out to European Turks as a group.

Moreover, even as the Turkish government cracked down on journalists in the weeks and days before the election, taking over entire media companies in keeping with their rankings as the world's worst country for press freedom, European leaders sat down with Erdogan and seriously discussed the possibility of bringing his country in to the E.U.

On a more general scale, Europe's schools rarely emphasize humanistic, secular values in their curricula – yet Islamic schools, many with radical viewpoints, continue to proliferate.

But perhaps more significant is the growing clash between European natives and Europe's Turkish population. "We don't feel Dutch," Volkan says. "We don't feel welcome here." He points to far-right, anti-Islam parties and to the silence of other politicians who fail to condemn them. When the AKP reaches out a hand saying, "we are here for you, we will protect you," by contrast, they are offering the welcome that Europe doesn't.

Herein lies the dilemma. Turkey welcomes its countrymen in Europe as part of a growing Islamization movement, while it is Turkey's secularists who feel unwelcome. Those secularists feel more comfortable with European values and ideals than are many of Europe's own Turks.

It would be easy to say of Europe's young Turkish population, "Well, then let them move to Turkey – good riddance" – as many do.

But that would be beside the point. The issue here is the ways that Europe is obviously failing. In the face of Erdogan's latest attacks on the free press, President Obama called on Turkish authorities to "uphold universal democratic values." If Europe cannot teach its own Turkish (and other Muslim) citizens to uphold those same universal values, then they will have only themselves to blame when Islam wins there, too.

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands.