Is this the real Arab Spring?

Shortly after the Nov. 13 terrorist attacks in Paris, Maryam Namazie, director of the Council of Ex-Muslims in Britain (CEMB), created the hashtag "#ExMuslimBecause" on Twitter. The result was a firestorm, through which tens of thousands of ex-Muslims across the world declared their apostasy, many gathering courage from the brave and often poignant words of others.

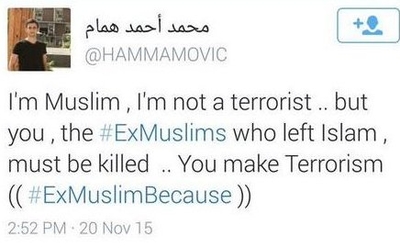

But just as quickly as their courage spread, the words of these former Muslims were soundly condemned by many others who remain within the faith. Tweeted someone calling himself @hammamovic, whose avatar shows a clean-shaven young man in a black T-shirt, "I'm Muslim, I'm not a terrorist, but you, the #exmuslims who left Islam, must be killed. You make Terrorism."

His words speak directly to the impetus behind Namazie's movement, and behind the founding of the CEMB, which, according to its website, was formed "in order to break the taboo that comes with renouncing Islam." That taboo is as powerful as it is perverse: For Muslims, leaving the faith is punishable by death.

Yet apparently, that risk of death is one many are prepared to take in order to continue with life on their own terms. And the number of such courageous ex-Muslims seems to be more than anyone anticipated. "By early Friday morning," reported Ali A. Rizvi, an #exMuslim himself who wrote about the phenomenon for the Huffington Post, "#ExMuslimBecause was the UK's top trending hashtag. We heard from secret LGBT Saudis; women who had been forced into marriages; closeted atheists in Egypt and Pakistan tweeting under pseudonyms young women disowned by their families in the US; and more."

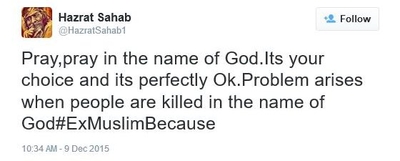

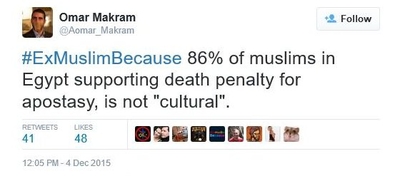

Among them were "@Yas" from Canada, who wrote: "#ExMuslimBecause my own mother told me I should be killed because I didn't believe the same things she did"; "@SamSedaei, who tweeted: "#ExMuslimBecause I was told I was a Muslim. But then I learned that religion is not a gene and being born to believers doesn't make you one"; and Rizvi himself, who posted, "#ExMuslimBecause No REAL God should need protection from bloggers and no REAL prophet should need protection from cartoons." Other notable posts include @LibMuslim's "#ExMuslimBecause misogyny, homophobia, stoning ppl to death and killing apostates don't suddenly become 'respectable' when put in a holy book" and Heina Dababhoy's "#ExMuslimBecause I got tired of suppressing my compassion twds LGBT+ people in the name of a deity claiming to be most compassionate." For her part, Maryam Namazie, who has been busy adding to the conversation, also observed, "#ExMuslimBecause my being unveiled is NOT the cause of earthquakes or other calamities."

But many Western Muslims who share their views have refused to take part, insisting that one can be Muslim and still support liberal ideals. "I do think that a lot of the questions that are coming out of the #ExMuslimBecause are issues that Muslims need to take on – such as gender equality and gay rights," says Ayesha Akhtar, a Bangladeshi-American artist and activist living in New York. The phenomenon is "complicated," she says, but adds, "I think that this hashtag and all the tweets, posts, stories that come out of it deserve a round of applause, especially from Muslims, who want religious freedom to dress and live according to their faith – because the right to religious freedom must correspond with the right to be free from any religious affiliation. In a truly liberal, tolerant society, one cannot be one without the other."

But many Western Muslims who share their views have refused to take part, insisting that one can be Muslim and still support liberal ideals. "I do think that a lot of the questions that are coming out of the #ExMuslimBecause are issues that Muslims need to take on – such as gender equality and gay rights," says Ayesha Akhtar, a Bangladeshi-American artist and activist living in New York. The phenomenon is "complicated," she says, but adds, "I think that this hashtag and all the tweets, posts, stories that come out of it deserve a round of applause, especially from Muslims, who want religious freedom to dress and live according to their faith – because the right to religious freedom must correspond with the right to be free from any religious affiliation. In a truly liberal, tolerant society, one cannot be one without the other."

Ibn Warraq, a particularly outspoken Muslim apostate and the author of Why I Am Not A Muslim, agrees, though he is skeptical that one can remain Muslim and still hold such secular, humanist viewpoints. The hashtag, he says, "will help those who think along similar lines. It will give them moral support, reassure them that they are not completely depraved, mad, or evil. They are not alone."

In other words, while it may seem like a mere Twitter trend, it's a trend that potentially has very real political punch. True, 25 years after the Salman Rushdie affair, Warraq observed via e-mail, "it is still impossible to avow one's atheism in public. All the atheists in the Islamic world keep their atheism online. But I think that is beginning to change."

This is of greater importance in the Muslim world than in the West where, for people like Akhtar, it is possible to consider oneself a practicing Muslim while maintaining Western ideas. That ability, in fact, is allowing many Western Muslims to start trying to change the narrative – one that, until now, has largely been led by conservative Islamic organizations such as the Council for American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) and by Muslim fundamentalists. Earlier this month, M. Zuhdi Jasser, founder of the American-Islamic Forum for Democracy, established the Muslim Reform Movement in concert with 13 other practicing Muslims, including activist Asra Nomani and Farahnaz Ispahani, a former member of the Pakistani Parliament. The group published a nine-point "declaration," confirming their shared belief in free speech, freedom of religion, equal rights and condemning violent jihad.

But such secular, contemporary viewpoints – let alone outright apostasy – would be impossible in an Islamic country, notes Warraq, who is also the founder of the Institute for the Secularization of Islamic Society (an organization that ironically bears the acronym ISIS). While it works in the West, ultimately, he says, "There is no Islam a la carte."

Yet even for Muslims in the West, there are risks. Some are excommunicated from their families. Others are attacked by Muslims in their communities, either physically, verbally, or emotionally. When Namazie spoke at Goldsmiths, University of London on Nov. 30 at the invitation of its Atheist, Secularist, and Humanist Society, for instance, the school's Islamic Society (ISOC) repeatedly disrupted. Making matters worse, Goldsmiths' LGBT and feminist societies defended the Islamic Society's actions.

Never mind that the ISOC supports the wearing of burqas and other garments that many claim oppress women. Never mind that Namazie, a woman, was bullied by (mostly male) Muslims in the audience. Never mind that the Islamic Society itself has invited speakers who defend jihadists, including Zara Faris, who frequently refers to events like 9/11 as "So-called 'Muslim' terrorist attacks.'" Never mind its support for the Boycott, Divest and Sanctions movement against Israel. Never mind that the Society accused Namazie of depriving its members their right to free speech in their efforts to protest against her, but failed to see an assault on free speech in their own efforts to silence her.

Never mind that the ISOC supports the wearing of burqas and other garments that many claim oppress women. Never mind that Namazie, a woman, was bullied by (mostly male) Muslims in the audience. Never mind that the Islamic Society itself has invited speakers who defend jihadists, including Zara Faris, who frequently refers to events like 9/11 as "So-called 'Muslim' terrorist attacks.'" Never mind its support for the Boycott, Divest and Sanctions movement against Israel. Never mind that the Society accused Namazie of depriving its members their right to free speech in their efforts to protest against her, but failed to see an assault on free speech in their own efforts to silence her.

Ironically, it is exactly Namazie's movement, says Warraq, that puts the lie to the concept of "Islamophobia" in the first place. "The unwritten subtext of such a charge is, of course, that the person so accused is ignorant, racist, and bigoted," he wrote in an e-mail. "But the existence of millions of Middle Easterners, and South Asians, who are now atheists refutes the claim that all those critical of Islam must be racists. Islam, in any case, is not a race. Second, the young Egyptians, Saudis, Iraqis and others who have firmly rejected Islam, have had experience of Islam from the inside; many of them have studied Islam to a very advanced level, and hence cannot be guilty of ignorance. And yes, they did read the Koran in the original Arabic. They know the social consequences of imposing Islam on the general populace: lack of freedom, those freedoms enshrined in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, and which we in the West take so much for granted. The charge of Islamophobia is an effective way of curtailing all rational discussions of Islam."

Goldsmiths notwithstanding, the response to #ExMuslimBecause suggests that Warraq may be right. If so, this would be an important step in the fight against Islamic extremism, because only if we can talk about the subject openly and frankly, debating the issue from all angles with the freedom that Western, enlightened culture holds as its core value, can we ever defeat those who would take that freedom from us.

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands.

Mona Haydar's "Hijabi Cool" Feminism Embraces the Islamist Patriarchy

Mona Haydar's "Hijabi Cool" Feminism Embraces the Islamist Patriarchy

Breaking News: CAIR Touts Partnership with Census Bureau

Breaking News: CAIR Touts Partnership with Census Bureau

CAIR Proves Irony is Not Dead

CAIR Proves Irony is Not Dead