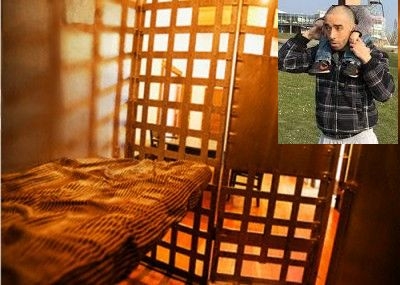

The initial reports regarding Islamic terrorist Karim Cheurfi, the man responsible for the latest attack that killed French police officer Xavier Jugele and wounded several others, contained the all-too-familiar phrase – "known to authorities."

The initial reports regarding Islamic terrorist Karim Cheurfi, the man responsible for the latest attack that killed French police officer Xavier Jugele and wounded several others, contained the all-too-familiar phrase – "known to authorities."

What actually was known? Cheurfi had a predisposition for violence, animosity toward authority – he had tried to kill police officers twice before – and a sense of alienation. They also knew that he had spent a significant period of his life in a place that some authorities called a radicalizing cauldron, the French prison system. Inside those prisons, a small group of Islamic terrorists was effectively radicalizing other inmates who came in as petty criminals with no religious leanings, said Pascal Mailhos, past director of France's domestic intelligence agency.

Mailhos' warning proved prophetic as French prisons spawned terrorists like Mohammed Merah, who in 2012 murdered police officers and Jewish school children in Toulouse, and Amedy Coulibaly, who killed a police trainee before storming the Hyper Cacher kosher supermarket and killing four hostages. Charlie Hebdo attacker Said Kouachi, like Karim Cheurfi, came out of the joint radicalized and ready to kill law enforcement, military personnel and innocent civilians in the name of Allah.

This problem is not unique to France. Former inmates who turned to the violent path of jihad plotted or carried out terrorist attacks in the United States, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany and the United Kingdom.

For some, particularly for those who have spent time in prison, the radicalization process from conversion to violence is more accelerated. "Some individuals, particularly those who convert in prison, may be attracted directly to jihadi violence...for this group, jihad represents a convenient outlet for (their) aggressive behavior," the Central Intelligence Agency said in a report, "Homegrown Jihad – Pathway to Terrorism."

When you combine the ingredients of violent aggressive behavior, animosity toward authority, incarceration, and radical Islamic ideology, you will almost certainly produce a deadly toxin. French prosecutor Francois Molins insisted that Cheurfi showed no signs of radicalization prior to the attack. Missing the signs could be the result of bad eyesight or, a lack of training. "We don't have anyone trained for anti-radicalization," said David Dulondel, the head of the union representing officers at France's Fleury-Merogis maximum security prison. "We can't say whether someone is in the process of radicalizing or not."

Despite an acknowledged problem with insufficient training, groups like the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) seek to censor any mention of Islamic radicalization from American law enforcement and military training.

In 2004, the FBI's official definition of radicalization was "the process of attracting and possibly converting inmates to radical Islam." They since have been pressured to change the term to "violent extremism."

Removing warning labels from canisters containing caustic material does not render the substance inside harmless. It only increases the risk of a deadly incident. Toxic waste spills are often the result of carelessness.

Prison radicalization should not be treated this way. We must put the tools in place to monitor and control this threat. Others have done it. Following last month's Westminster Bridge attack by Khalid Masood, British authorities announced the formation of a task force that will combine intelligence, law enforcement, corrections and probation personnel to look at literature, clergy, and other influences available in prisons. The task force will also closely monitor recently released inmates for changes in behavior or association with known radical mosques or people. France, which has suffered its share of jihadi violence carried out by ex-inmates, had to admit that its program to address prison radicalization had been an utter failure. Yet it has not made any significant changes.

Here in the United States, it is imperative that the Justice Department and the FBI revise the Correctional Intelligence Initiative Program to include the proper vetting of clergy and a post release component to track people who were radicalized or previously incarcerated for terrorist crimes. The initiative started in 2003 with a mission to "detect, deter, and disrupt efforts by terrorist and extremist groups to radicalize or recruit within all federal, state, territorial, tribal and local prison populations."

Failure to effectively address the ongoing threat is not an acceptable option. At some point there will be a price to pay.

IPT Senior Fellow Patrick Dunleavy is the former Deputy Inspector General for New York State Department of Corrections and author of The Fertile Soil of Jihad. He currently teaches a class on terrorism for the United States Military Special Operations School.