Strategically, Hamas remains as committed as ever to its objective of destroying Israel and toppling the Fatah-run Palestinian Authority in the process. Tactically, however, Hamas exhibits pragmatism and won't rush into wars with Israel when conditions are ill suited.

Strategically, Hamas remains as committed as ever to its objective of destroying Israel and toppling the Fatah-run Palestinian Authority in the process. Tactically, however, Hamas exhibits pragmatism and won't rush into wars with Israel when conditions are ill suited.

Hamas looks at the long run, and remains convinced that it can eradicate Israel, even if it takes decades or centuries. Yet it would prefer to bide its time, and build up its force until the next clash while working to decrease its acute regional isolation. For this to happen, Hamas needs to avoid plunging Gaza into a new war any time soon. Yet it remains far from clear that it will be able to do this.

Should a war erupt in the near future, it likely will be triggered by unplanned dynamics of escalation.

Gaza's woeful living standards and infrastructure are among those factors. Crises such as the ongoing electricity supply problem plaguing the Strip could facilitate an early conflict, as Hamas may try to distract the population's frustrations from its failings, and divert them to Israel.

The Palestinian Authority (PA) is threatening to make matters worse by cutting off cash for Gaza's power plant. It's part of the ongoing feud between the Fatah-run PA in Ramallah and Hamas in Gaza. Gazans now receive electricity only four to six hours a day due to this feud. In January, Gazans took the unprecedented step of protesting power cuts, making Hamas extremely nervous.

In addition to tensions over the electricity crisis, a Hamas-run terror cell could spark conflict if it carries out a mass casualty attack that spawns Israeli retaliation.

The sheer scope of such plots that Israel thwarts every year is enormous.

Last year, 184 shooting attacks, 16 suicide bombings, and 16 kidnapping plots were foiled, Shin Bet chief Nadav Argaman testified last month before the Knesset's Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee. Hamas had "significantly increased" efforts to pull off attacks in the West Bank and in Israel, he said, adding that Israeli security forces arrested more than 1,000 Hamas members in the West Bank last year and broke up 114 cells.

These are risks Hamas is prepared to take, since the day that it ceases all attempts to carry out jihadist terrorism against Israel is the day that it stops being Hamas.

Yet Hamas is also a government now, and it must consider the Gazans it rules. Hamas is keenly aware of Palestinian sentiment. Its leaders grew up in Gaza's refugee camps and always have their finger on the pulse of Gazan society.

Hamas leaders seem to understand that the public opposes a new damaging war with Israel. They recognize that the Palestinian public cannot stomach a war with Israel every two years. The reconstruction program in Gaza following the 2014 conflict is far from complete. There are still Gazans whose homes haven't been repaired from the damage inflicted in 2014.

The general population, despite being exposed to Hamas's daily propaganda diet of jihadist rhetoric, would likely be reluctant to be again be used as human shields by the military wing, barely three years since the end of the last clash.

The price of Hamas's policy of embedding its rocket launchers and fighters in Gaza's civilian areas also is not alluring to many Gazans.

On the flip side, one of Hamas's worst fears is of being perceived as weak. After one of its senior operatives was mysteriously killed recently, it executed three people it accused of collaborating with Israel.

Hamas also responded to Mazen Fuqaha's killing by sending threatening messages to Israel promising vengeance. Hamas videos suggest it will target senior Israeli security officials for assassination.

Fuqaha was a key figure in the Izzadin Al-Qassam Brigades, and reportedly in charge of setting up multiple terrorist cells in the West Bank. His bullet-ridden body was found last month outside of his Gazan apartment building.

The Israeli defense establishment takes these Hamas threats seriously. Despite the noise, however, Hamas has not rushed to respond just yet – underlining the fact that Hamas is aware of the restraints factors that it is under.

Since the end of the 2014 war with Israel, the Islamist regime has shied away from escalating the security situation with Israel.

Hamas's leadership sees unfavorable regional conditions. They lack any powerful regional backer following the 2013 downfall of Muhammad Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood president in neighboring Egypt, in whom Hamas staked so many of its hopes.

In the past, Hamas enjoyed many partnerships, enjoying arms support and funding from the Shi'ite axis (Iran and Hizballah) – and forming relationships with Sunni powers.

But the Middle Eastern regional upheaval, which pits Sunnis against Shiites, and Islamists against non-Islamists, forced Hamas to make choices. It could no longer be on the same side of both Shi'ite Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia, who are locked in a transnational proxy war. In the same vein, Hamas cannot be on the same side as both the Assad regime and the Sunni rebels fighting to remove him.

Worst of all from Hamas's perspective, Morsi's departure means it cannot rely on its primordial impulse to attach itself to a Sunni Muslim Brotherhood-led backer.

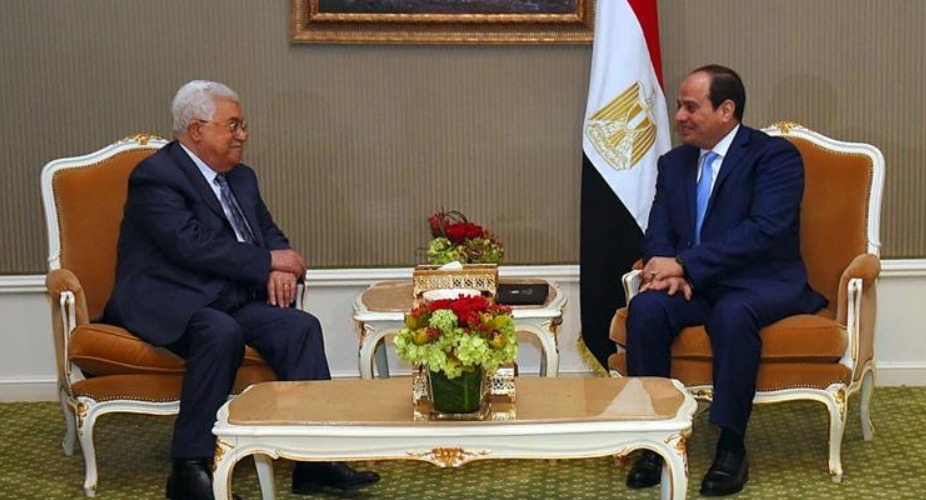

Five years ago, there were initial signs of a regional wave of Muslim Brotherhood successes. The Brothers rose to power in Egypt, Turkey, Tunisia, and had Qatari backing. Morsi's 2013 fall changed Hamas's fortunes for the worse. The rise of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, a leader who identifies Hamas as a Gazan branch of his domestic arch-enemy, the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, guaranteed Hamas's isolation.

Relations with Cairo remain rocky despite recent Hamas attempts to improve ties. Egypt may open its Rafah border crossing a few days a week, but this does not change its core view of Hamas as a true enemy, to be held at bay, weakened, and deterred.

Hamas has also fallen out with Saudi Arabia. And Hamas and Iran do not get along very well either, despite Iran continuing to be the chief sponsor of the military wing, paying it $50-$60 million a year, according to various estimates.

This leaves Hamas with just two stalwart friends: Qatar and Turkey, neither of which can back them substantially. Turkey is not an Arab state, meaning that its role in the Arab world is limited, and its desire to lead the Arab world will always be met with suspicion. A failure by Turkey to infiltrate the region means that it can only do so much to assist Gaza. Qatar, though wealthy, is politically weak, and geographically distant.

New Hamas leader Yihyeh Sinwar, despite his fundamentalist inclinations, must consider these constraints and see that his Islamist-run enclave has little real backing.

To compound its problems, Hamas also has serious financial issues. It has three main sources of income: Donations from states, donations from private individuals, and Hamas's network of investments.

Hamas gets far less money than it used to from its donors, according to Israeli assessments. Only Qatar and Turkey donate on a regular basis, while Iran continues to finance the military wing, but not the entire movement.

Hamas is a large organization, with operations in the West Bank, Qatar, and Turkey in addition to Gaza. In the Strip, it needs to pay salaries, and prepare for its next clash with Israel. Hamas also seeks to export terrorism to the West Bank and build up political support among West Bank Palestinians. All of this costs money. It is has offices and headquarters in multiple states overseas that require annual budgets.

Private Gulf State donors are drying up. Wealthy Saudis are more interested in supporting Syrian rebels. Hamas's cause has moved to the back of the line.

Its investments, meant to be saved for a rainy day, now must be tapped.

So what can Hamas do? First and foremost, it continues its domestic military build-up, mass producing rockets, mortar shells, variants of shoulder-fired missiles, drones, and digging tunnels – all at the expense of the welfare of the 2 million Palestinians it rules.

That's because Hamas drew many operational lessons from its last conflict with Israel, and is keen on rebuilding its terrorist-guerrilla army without interruptions.

One lesson was to focus on a perceived Israeli vulnerability through short-range strikes. To that end, it is building new rockets that carry 200 kilogram warheads - significantly larger than past rockets made in Gaza.

These projectiles are not accurate, but would cause enormous damage if they slammed into a southern Israeli town or village.

Hamas weapons factories produce simple RPGs as well.

Second, Hamas is trying to becoming more 'acceptable' to the region and to the world. It is about to unveil a new charter which will be an attempt to obfuscate its jihadist ideological leanings and ties with the Muslim Brotherhood, and present itself as being merely a national "resistance" organization.

In the long run, Sinwar and his regime plan to continue to prepare for the 'grand' destiny they have chosen for Gaza. So long as Hamas rules Gaza, it will be the base of unending jihad against Israel, buffered by tactical ceasefires, until conditions are ripe for a new assault.

Yaakov Lappin is a military and strategic affairs correspondent. He also conducts research and analysis for defense think tanks, and is the Israel correspondent for IHS Jane's Defense Weekly. His book, The Virtual Caliphate, explores the online jihadist presence.

Why Egypt Works to Curb Hamas' Influence in Gaza

Why Egypt Works to Curb Hamas' Influence in Gaza

Hamas-Driven West Bank Violence Targets Israel and the PA

Hamas-Driven West Bank Violence Targets Israel and the PA

Budding West Bank Hamas Cell Aimed for Major Bloodshed

Budding West Bank Hamas Cell Aimed for Major Bloodshed