The theater of the absurd will soon have a new actor if convicted Islamic terrorist Ahmad Rahimi has his way. Rahimi has asked to be allowed to take a variety of prison programs while serving a life sentence for setting off several bombs in the New York-New Jersey area in 2016.

The theater of the absurd will soon have a new actor if convicted Islamic terrorist Ahmad Rahimi has his way. Rahimi has asked to be allowed to take a variety of prison programs while serving a life sentence for setting off several bombs in the New York-New Jersey area in 2016.

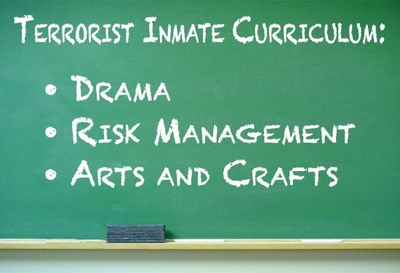

He has been taking a drama class while in Manhattan's Metropolitan Correctional Center, his lawyer Xavier Donaldson told U.S. District Judge Richard Berman. He would like to continue to pursue this and enroll in several other educational programs in business and enterprise risk management.

Unfortunately, that's not all he's been doing in MCC. Rahimi has been radicalizing other inmates to his jihadist cause in the prison mosque. He also has shared instructions on how to build an improvised explosive device with his fellow inmates.

Realizing that, as the prosecutor in his case wrote, Rahimi "continues to attempt to wage jihad from his prison cell..." What prison rehabilitation program would best address his situation? Basket Weaving for Bombers?

The stark reality is, there is none. Two years ago, Assistant Attorney General for National Security John Carlin acknowledged that neither the Bureau of Prisons nor the DOJ had a program that successfully dealt with incarcerated terrorists, and a recently released study from George Washington University's Program on Extremism confirmed that. The study went on to warn that the continued failure to have an adequate de-radicalization program would only increase the threat of radicalization in prison.

Why is there such reluctance to initiate a much needed program? What irrational thinking drives some to oppose facing the threat of radicalization head on?

When the FBI attempted to initiate a program that would address radicalization in society as a whole, particularly involving young people who were most vulnerable to the allure of groups like ISIS through the internet, it was met with stiff resistance from several groups including the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, which felt the program singled out Muslims.

In some cases, defense attorneys have raised concerns that any de-radicalization program that attempts to change an inmate's religious beliefs, even those as twisted as a committed jihadist, would violate both the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and the First Amendment.

Several convicted terrorists in U.S. prisons have already sued the Bureau of Prisons over that very issue, including American Taliban fighter John Walker Lindh and underwear bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab. So perhaps it's a fear of continued litigation that hinders the development of any viable de-radicalization program that terrorists in prison would be required to attend.

What if the program were voluntary? In the United Kingdom, the overwhelming majority of inmates convicted of terror crimes simply refused to attend any de-radicalization program and still were released from prison.

The GW study notes that there are 140 people in prison for supporting ISIS. Add to that the hundreds of others who supported Islamic terrorist organizations like al-Qaida or the Taliban, and have been incarcerated for decades, and one wonders what – if anything – has been done while they were in prison to lessen the threat their beliefs pose.

Are terrorists like 1993 World Trade Center bomb plotters El Sayyid Nosair and Mohammed Salameh, or would-be al-Qaida bombers Jose Padilla and Richard Reid, or countless others being exposed to any therapeutic program specifically designed to correct their jihadist behavior?

More than 300 ex-cons who were in prison for terror-related crimes now walk the streets. They served their time and were released. Does anyone know exactly where they are? Is there a post-release registration program that notifies law enforcement agencies when someone who has been convicted of terrorism moves into their community? We do it with sex offenders. Why not terrorists?

Given that the vast majority of people convicted of terrorism crimes are not serving life sentences and that as many as 100 of them will be released in the coming years, the Department of Justice must act quickly to remedy the situation.

The Bureau of Prisons' response to the GW study was to claim that "prisoners linked to terrorism have access to programs...including education and vocational training."

Maybe. But Macramé for Terrorists isn't the solution to the continuing threat of prison radicalization.

IPT Senior Fellow Patrick Dunleavy is the former Deputy Inspector General for New York State Department of Corrections and author of The Fertile Soil of Jihad. He currently teaches a class on terrorism for the United States Military Special Operations School.