She was a 15-year-old student at San Antonio's Taft High School with a soft smile and dark eyes. Like most girls her age in Texas, she favored blue jeans. Unlike most girls her age in Texas, in 2017 she was promised in marriage to a man 10 years her senior, who would pay her parents $20,000 to take her as his wife.

She was a 15-year-old student at San Antonio's Taft High School with a soft smile and dark eyes. Like most girls her age in Texas, she favored blue jeans. Unlike most girls her age in Texas, in 2017 she was promised in marriage to a man 10 years her senior, who would pay her parents $20,000 to take her as his wife.

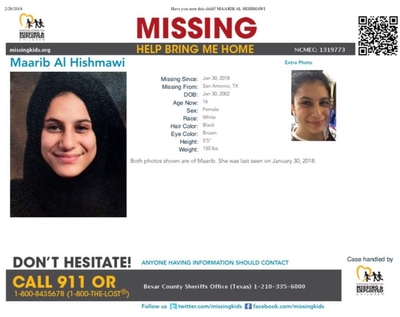

But the Iraqi-born Maarib Al Hishmawi had no intention of marrying so young, least of all to a man so much older and whom she hardly even knew. She refused.

Her parents, who had moved to the United States from their native Iraq two years prior, were furious. They "choked her almost to the point of unconsciousness," said Bexar County Sheriff Javier Salazar. They beat her with broomsticks. Her mother, 33-year-old Hamdiya Sabah Al Hismawi, threw hot oil on her body.

Maarib escaped, running away from home in January. Claiming they feared she'd been kidnapped, her parents called in local police and the FBI to help track her down. But even from the start, Salazar told CBS News, it was clear to him that "this wasn't an ordinary missing persons case." When police found her in an undisclosed location some weeks later, Maarib explained her story. She and her five brothers were taken in by Child Protective Services and her parents immediately taken into custody. Her father blamed Maarib for his arrest.

This is not just a story about domestic abuse. It is a story about cultural mores, institutionalized violence against women and girls (and occasionally young men) in the name of family honor. And it happens to thousands of them every year, not just in places like Afghanistan and Somalia and Iraq, but in America, England, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, France, and elsewhere across the Western world.

Honor violence, according to Phyllis Chesler, the author of A Family Conspiracy: Honor Killings and several studies on the subject, is a form of "tribal violence." It differs from domestic abuse in that honor violence involves "carefully planned conspiracies and may be perpetrated by multiple family-of-origin members." Honor violence also differs from domestic abuse in aim: rather than violence directed at a woman's immediate behavior, such as coming home late, or failing to serve a perfect meal, honor-based violence aims to punish women who "are seen to be acting too 'western' or who have relationships or friendships which transgress gender, caste, ethnic or religious distinctions," according to a 2008 CIVITAS report. "Women's behavior which is viewed as 'unacceptable' by families and communities can include having a boyfriend of different race, religion, caste or wearing 'western style clothing and listening to 'western' music."

Such violence is also not limited to Muslims, says Jordanian journalist Rana Husseini, author of Murder in the Name of Honor. "While some Muslims do murder in the name of honor – and sometimes claim justification through the teachings of Islam – Christians, Hindus, Sikhs and others also maintain traditions and religious justifications that attempt to legitimize honor killings," she writes.

Weapons of choice often differ from non-honor-related abuse, involving acid attacks, burning, or hot oil as with Al Hishmawi. Many rights organizations, including the Ayaan Hirsi Ali (AHA) Foundation, also consider forced marriage and female circumcision, or FGM, to be forms of honor violence.

While Chesler's work focuses on honor killing and not honor violence in general, her observations about the nature of honor killings applies as well to honor violence. "Brothers, uncles, fathers, and other male relatives usually commit the murder, although mothers have also been known to collaborate in the murders of their daughters; sometimes, they are even hands-on perpetrator," she said in a recent e-mail. By contrast, "Batterers who murder in the West are usually acting in an unplanned and spontaneous way. They alone are the perpetrators. Their own families do not assist them nor does the victim's family of origin." Moreover, she adds, "In the West, batterers and wife killers are not celebrated—they are shunned. If possible, they are also prosecuted." Yet those who commit honor killings and honor violence, she said, "are viewed as heroes who have saved their family's honor. Thus, they feel no shame or remorse."

Indeed, even the victims may feel they "deserve" their fates, or at least show understanding of their abusers. When 19-year-old Aiya Altameemi was spotted talking to a boy near their home in Phoenix, Ariz., her mother and sister padlocked her to a bed so she could not escape and then beat her severely. Officials handling the case learned later that Altameemi's father also once held a kitchen knife to her throat and her mother burned her with a hot spoon when she refused an arranged marriage. Yet at their trial, Aiya wailed that she wanted her mother back, and later defended her to reporters. "We are Muslim," she said. "Our culture says no talking to boys."

While growing attention to the phenomenon of honor killings has led to greater oversight by most Western governments, many of which now recognize such murders as a distinct category, honor violence remains largely overlooked and misunderstood. Too often it is grouped with domestic violence, which ignores the true and most insidious nature of the threat. Those facing honor violence have nowhere to run – not their mothers, their sisters, their imams. Consequently, treating the problem of honor violence is far more complicated than handling domestic abuse, or simply putting the husband or other family in prison.

What's more, Western countries are only now starting to recognize the magnitude of the problem, said Amanda Parker, senior director of the AHA Foundation, an organization that fights honor violence, female genital mutilation and forced marriage. "Across the board, when you see the data being collected in each of the countries, the consensus from experts is that the estimates are low because these are crimes that are not reported, are kept under wraps within families and then there is a judgment call among those who are collecting the data," she said in a recent phone conversation. "Are they going to actually define it as 'honor violence'?"

Even official estimates can vary widely. In the Netherlands, the only country with a special police force dedicated to honor crimes, officials registered 452 incidents in 2015. But police receive approximately 3,000 reports of honor-related violence each year, claims criminologist Janine Janssen of the National Expertise Center for Honor Related Violence and author of the Dutch handbook Focus on Honor. According to Dutch newspaper the Volkskrant, 80 percent of these incidents take place in Turkish-Dutch families, 20 percent in Dutch-Moroccan, and 10 percent in Iraqi, Afghan, and Kurdish homes. Others occur in families with roots in the Balkans, Syria, Somalia, Pakistan, and in Hindu families from Suriname.

These numbers seem relatively consistent Europe-wide. In the UK, for instance, the Iranian and Kurdish Women's Rights Organization (IKWRO) registered 2,823 incidents in 2011, a 57 percent increase over 2010. It is not clear whether the increase in reported assaults is due to an actual rise in the number of incidents, increased bravery among victims in reporting, or better awareness of the problem by law enforcement itself.

And in Sweden, where in 2016 a man cut off his wife's nose and upper lip before stabbing her 66 times in her home, 97 people were serving time for honor-related crimes, according to a 2017 State Department report. A separate 2007 report estimated that 1,500-2,000 women "had been subjected to honor-related violence" that year alone, exclusively among Muslim immigrant families. The State Department report quotes cabinet minister Nyamko Sabuni, a Congolese immigrant, as saying that honor violence against women had reached "urgent proportions."

None of these figures, however, seem to reflect the problem of FGM, which is at least as urgent in the West. "Forced marriage and female genital mutilation are acts of violence in that they are acts of physical or emotional force that are intended to preserve or improve the family honor," said an Honor Violence Study Report produced by the Maryland-based research outlet WESTAT. The numbers are shocking. The State Department report cites data showing 53,000 victims in France, most of whom were "recent immigrants from sub-Saharan African countries." In Germany, the numbers are similar, at an estimated 48,000 victims, with about 9,000 adolescent girls at risk; and in the Netherlands, an estimated 29,000 have suffered FGM, with 40 to 50 young girls are still at risk each year according to a 2013 report.

Although FGM is illegal in all of these countries, prosecution is sporadic. "Despite having legislation in place since 1985, the United Kingdom has failed to prosecute any perpetrators of FGM," the AHA Foundation noted, this while the country recorded 5,391 incidents in 2016-2017. Moreover, "only 26 states in the US specifically ban FGM," the foundation reported last month, yet more than 110,000 women and girls at risk live in the 24 states that do not. Worse: according to Amanda Parker, "The Centers for Disease Control estimates that more than half a million women and girls are at risk of FGM in the US." And if that's just for FGM, she says, "the numbers facing honor violence have to be giant."

Parker and others are also concerned that recent immigration crackdowns in the United States may make the matter worse, as immigrant women and girls become more fearful of seeking help. And the lack of training among law enforcement makes it difficult to prosecute honor crimes when women do report them. "The main thing is that those who are best-placed to count these incidents are really law enforcement, and they aren't sure what they're looking at when they see it," she says. Training, as has been done in the Netherlands, is therefore crucial. "If there were a box they could tick that said 'reclaiming family honor,' that would work," notes Parker, "but we are very far from that at this point."

Still, she and other activists against honor violence remain hopeful. "As slowly as things are moving," says Parker, "they are actually moving."

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands. Follow her at @radicalstates.