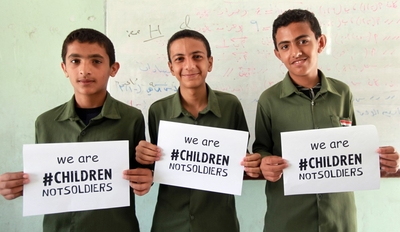

UN image |

There is 13-year-old Younis, who was taught to use a machine gun as a child, according to a CNN profile, and Saleh who drove rocket launchers, also at 13. And 13-year-old Basheer fired Katyusha rockets at the "infidel enemy" – Yemen's government forces who are backed by Saudi Arabia, the United States, France, and the UK.

All are or have been part of Yemen's growing child armies, children recruited to fight on both sides of the city's four-year-old civil war. The United Nations has reported child soldiers as young as 11. Many are sent by their parents, either for the high salaries soldiers receive, or hopes that the children will achieve martyrdom.

As the war there rages on, children are the most victimized. Besides the boys who become soldiers, there are the girls who are sold off as wives, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres told a conference in Geneva last spring. "Nearly two-thirds of girls are married before 18, and many before 15." In addition, food, water, and medication shortages mean that "every ten minutes, a child under five dies of preventable causes," he said. The UN has declared Yemen "the world's worst humanitarian crisis."

The use of child soldiers is hardly unique to Yemen. A newly-released UN Security Council Report describes a "large increase" of recruitment of child soldiers in 2017 over 2016, primarily in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (1,049), Somalia (2,127), and South Sudan (1,221).

Other cases include Afghanistan, among the Taliban and the local ISIS branch (known as ISIL-KP or ISKP, for the Islamic State in Iraq and Levant Khorasan Province). Recruitment of child soldiers there surged in 2016, when Taliban leaders "used madrasas, or Islamic religious schools, to provide military training to children between the ages of 13 and 17, many of whom have been deployed in combat," according to Human Rights Watch (HRW). Indoctrination begins when boys are 6 years old; by age 13, HRW reports, they are capable of using firearms and IEDs. As in Yemen, families are often attracted to the Taliban madrassas for economic reasons: The Taliban provides food and clothing, and the parents may also receive payments in return for enrolling their children in the schools.

ISIL-KP works similarly in both Afghanistan and in Pakistan, where it was formed after breaking from the Pakistani Taliban. While 9-year-old boys train to shoot AK47s, their parents receive salaries from the ISIL leaders, who also cover children's food, clothing, and other costs. As in the Islamic State's well-known "cub" camps, young boys in ISIL-KP strongholds are indoctrinated early and raised to form a jihadi generation. They are trained to whip prisoners, to behead infidels, to shoot. One teenage soldier for ISIL-KP told Voice of America "we saw a lot of people slaughtered. We also wanted to slaughter someone because we were told that this would bring us holy rewards from God." ISIL-KP commanders, he said, also regularly showed the local residents videos of the infidels oppressing Muslims," a tactic aimed at raising a desire among local youth to defend the Muslim ummah, or community.

Nowhere, however, is the use of child soldiers more dire than in Somalia, where the UN verified 2,127 recruits in 2017 alone, adding significantly to the 6,163 children recruited between 2010 and 2016. More than 70 percent fight with Al Shabaab, an al-Qaida affiliate which HRW claims recruits children as young as eight years old for indoctrination and military training in terrorist-run madrassas similar to those in the Islamic State and Afghanistan. And even 9-year-olds, VOA has reported, are used "as cannon fodder." Al Shabaab leaders also frequently demand that communities enlist their children "or face attack," and have been known to kidnap adults who refused to hand the children over, using the children themselves as ransom. Hundreds of youths have also been abducted from schoolrooms and local religious schools allegedly used to recruit child soldiers.

And it isn't only boys. According to a 2015 UN report, up to 40 percent of child fighters are girls, who are enlisted as suicide bombers, sex slaves for male soldiers, weapon smugglers, or even for combat, as in Uganda's Lord's Resistance Army. Often they, like boys, may be used as human shields – a tactic particularly favored by Hamas. Others, such as the American and European Muslim girls who have joined ISIS or the girls of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) enlist voluntarily, either for ideological reasons (the girls who join ISIS) or to escape poverty and oppression at home (the young women of the DRC). Yet they, too, frequently are subjected to sexual abuse in addition to the traumas of life in a war zone and the often gruesome acts of killing, torture and terror.

The effects of those traumas do not end, however, just because the war does. Child soldiers may suffer lifelong effects of PTSD. Others, radicalized from their earliest years, hold tight to their indoctrination and seek out other groups sympathetic to their cause as they grow older. Others who return home find that they are not welcomed back as heroes, but rather, are ostracized and shunned.

This is particularly true for the girls, who may have been raped and are rejected by their families and communities as no longer "pure." These girls, sometimes pregnant, sometimes already mothers, often afflicted with STDs, are traumatized by their lives on the front. Yet the shame that accompanies their homecoming may lead them to "rejoin the very armed groups that abused them," according to IRIN, an organization that focuses on reporting about humanitarian crises.

Other child soldiers, either alone or with their parents, occasionally seek asylum in the West. But there, as for the returning "cubs" of the Islamic State, concerns about security may force them back again. What do you do, after all, with a 15-year-old boy who has been trained from the age of 8 to wage jihad, and is capable of making, planting, and exploding an IED?

Many organizations have struggled to address these problems, including UNICEF, War Child, and Child Soldiers International. Their efforts focus on deradicalization, re-integration of returning child soldiers, strengthening communities to protect against child abduction, and other local projects.

Yet the question still remains: are these children dangerous warriors, to be kept from the community at all costs – or are they the victims, needing to be embraced?

No one yet has determined the right answer. And so the cycle continues, and the crisis only grows.

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands. Follow her at @radicalstates.