As more foreign fighters return from the ISIS battlefields to their home countries and face possible prosecution and imprisonment, the European Union continues to wrestle with how to deal with Islamic radicalization within its prisons.

As more foreign fighters return from the ISIS battlefields to their home countries and face possible prosecution and imprisonment, the European Union continues to wrestle with how to deal with Islamic radicalization within its prisons.

American policymakers need to pay attention because it's a challenge we face, too.

"We found a lot of people that maybe weren't convicted on terror-related charges were radicalizing in the prison systems," U.S. Rep. Mike McCaul said last month. "I think the Bureau of Prisons needs a program to ensure that radicalization is not taking place because it is."

A recent investigation by Spanish counter terrorism officials uncovered a jihadi recruitment network operating inside 17 of its prisons. The group recruited and radicalized new inmate converts and planned to carry out several attacks when some of its members were released.

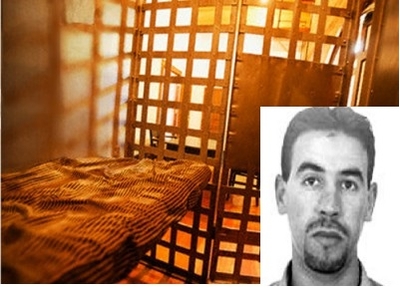

Group leader Mohammed Achraf is a 44-year-old Moroccan serving time for plotting terror attacks. The Gatestone Institute closely examined Achraf's history, finding that he had organized a terror cell during a previous prison stint. He formed the "Martyrs of Morocco" in 1999, a radical Islamic network operating in five prisons. Achraf was released in 2002, but arrested just two years later in the wake of the 2004 Madrid train bombing which killed 191 people and injured nearly 2,000. Resulting investigations uncovered a Martyrs of Morocco plot to blow up Spain's National Court with a truck loaded with more than 1,000 lbs. of explosives. The terrorists wanted to destroy evidence that was being relied upon to prosecute the Madrid terror cell.

Ironically, prior to the planned attack Achraf was in contact with an Islamic terrorist in the United States. Mohammed Salameh, convicted in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, was able to smuggle out correspondence to Achraf from his prison cell in the Bureau of Prison's Super Max facility in Florence, Colo., proving that for the committed terrorist, prison walls do not stop jihad.

Achraf was scheduled to be released from prison last Sunday, but he was placed in solitary confinement after the discovery of his radical activities in prison and could face new criminal charges.

What is the attraction that draws common criminals to radical Islamic ideology and jihad while incarcerated? Some authorities suggest that it is the individuals' predisposition to violence and their animosity toward authority that can turn prisons into incubators for terrorism. Others point to the inability of second and third generation Muslim immigrants in the EU and the United States to successfully assimilate into Western society. This failure to fully embrace life in the West and the feeling of alienation spirals downward to petty criminal activity, incarceration, and exposure to the influence of convicted Islamic terrorists already in the prison system.

The need for continued research on the causes of radicalization and ways to effectively neutralize it recently suffered a setback in the United Kingdom when the Ministry for Justice rejected a proposal to study why inmates who convert to Islam in prison are susceptible to radicalization. Supporters of the proposed academic study which included Max Hill, the UK's independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, felt that the ministry feared that the outside study would expose the British prison system's shortcomings in dealing with the rising violence and intimidation toward other inmates by radicalized Muslim prisoners.

Despite that development, the study has been approved for use in two other EU countries' prison systems, France and Switzerland, but it will suffer for the absence of British data.

Rejecting academic studies that might shed light on understanding social maladies is a step backwards. But we've seen that happen in the United States, when groups like the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) demanded that the New York Police Department no longer be allowed to reference a study, "Radicalization in the West," when trying to deal with terrorism. New York Mayor De Blasio ceded to the group's demands last year.

But several congressional leaders are pushing to pass the Tracer Act, which would allow monitoring of Islamic radicalization in the prison and create a registry of convicted terrorists upon their release. The information gathered would then be shared among federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies.

The EU would be wise to consider similar legislation.

Terrorism knows no boundaries. Neither does the radicalization process. A cohesive strategy among Western democracies that combines both research and effective anti-terrorism laws is necessary to counter it.

IPT Senior Fellow Patrick Dunleavy is the former Deputy Inspector General for New York State Department of Corrections and author of The Fertile Soil of Jihad. He currently teaches a class on terrorism for the United States Military Special Operations School.