Thirty years ago, on Feb. 14, 1989, the Iranian cleric and politician Ayatollah Khomeini formulated his famous fatwa against British author Salman Rushdie. He sentenced to death not only the writer of The Satanic Verses (1988) but also "those involved in the publication" of the book; so even publishers and translators. With one stroke of his pen, Khomeini became the originator of a new type of terrorism, theoterrorism. He threatened with violence the citizen of another state with his aim to undermine the central structures of democratic society, freedom of speech. And he did this, according to his own pretense, on divine command and with divine authority (theos = god, so hence theoterrorism).

Since that fateful moment in the history of liberal democratic societies, some sort of asymmetric warfare began between nation-states and networks of terrorist organizations or terrorist "lone wolves." The world has not yet found any solution for that pernicious problem.

Cartoon wars

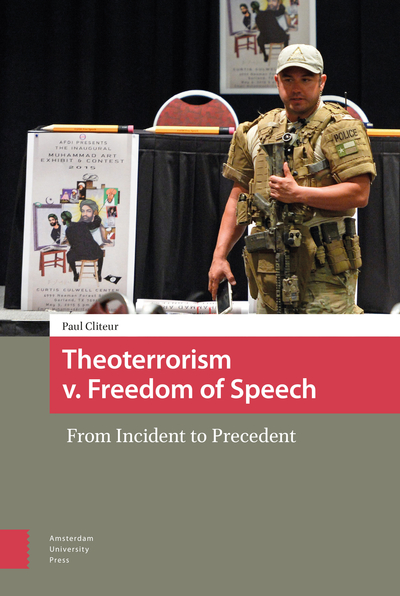

Let me give a contemporary example from the American context. On May 3, 2015, two heavily armed theoterrorists, Elton Simpson and Nadir Soofi, tried to force their way into an American cartoon contest focusing on Islam's prophet Muhammad in Garland, Texas. After opening fire, both were killed by security personnel. More recently in my own country, the Netherlands, a Dutch cartoon affair started when the Dutch politician Geert Wilders, present during the American cartoon contest, decided to organize his own Muhammad cartoon contest within the precincts of the Dutch Parliament. This proved more difficult than expected. On Aug. 31, 2018, an Afghan national named Jawed S., traveling from Germany and with a German residency permit, stabbed two American tourists in Amsterdam Central Station. He had come deliberately to the Netherlands to carry out his attack because of Wilders' cartoon contest. He told police that he made the trip because he wanted to avenge four types of offense (or insult) that the cartoon contest committed. First, he noted that the Prophet Mohammed had been insulted. Second, he claimed that the Quran had been insulted. Third, Islam had been insulted. Fourth, Allah had been offended in the Netherlands.

"S." – Dutch courts do not release defendants' surnames – is on trial for his act of terrorism. Even before the attack, Wilders decided to cancel the cartoon contest, not because of his own security risk (he is in a 24/7 security program), but for the security of others.

No solution

What do all these events tell us? They say that people noticed Khomeini's new terrorist tactic, introduced in 1989, and continue to apply it. Liberal democratic societies have, so far, showed no other reaction than giving in to terrorist demands. Thirty years after Khomeini's fatwa, and 40 years after the Iranian Revolution, we see a long series of (so far failed) appeasement attempts. When Theo van Gogh was killed by a jihadist in 2004, the minister of justice proposed revitalization of blasphemy laws. Most of the Danish cartoonists involved in a 2005 controversy did not speak out about why they published their cartoons. Only one of them does, Kurt Westergaard, and he is in a 24/7 protection program. The cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo are dead, the magazine is on the brink of bankruptcy.

What has not been revealed in the literature on the Rushdie Affair so far (Kenan Malik, Daniel Pipes, Brian Winston, and others), is that it did not start with Rushdie on Feb. 14, 1989, but two years earlier with the Dutch television host Rudi Carrell. Carrell had a show on West German television and was famous for poking fun at politicians. He once included a 14-second gag in 1987 mocking Ayatollah Khomeini that sparked a diplomatic row.

Carrell received police protection after he was threatened. Iran's ambassador complained that the bit insulted religious feelings of Muslims "all over the world." He demanded apologies from the West German government.

When Dutch television prepared to broadcast the clip as part of a news program, something unusual happened: Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs Hans van den Broek called the Dutch broadcaster trying to convince the host to drop the Khomeini spoof. And with success. The television company did not air the item discussed.

At the least, airing the Carrell spoof will trigger a similar diplomatic crisis, van den Broek argued. "[G]iven the fact that these consequences have become reality in Germany, I say that we, you and me, should ask ourselves: is this worth it?"

It seems not unduly speculative to assume that in this particular moment the Iranian dictator knew that he had developed a new highly successful terrorist tactic. You do not even to have to take people hostage anymore. Issuing death verdicts (Rushdie) or threats (Carrell) is sufficient to force liberal democracies into submission. Call it modern hostage-taking. Liberal democratic societies have struggled with this ever since.

Paul Cliteur is a professor of jurisprudence Leiden University (the Netherlands) and author of the forthcoming Theoterrorism v. Freedom of Speech.