At 23, her first book now tops the country's bestseller list – an autobiographical novel praised by critics nationwide. She has been featured in interviews on TV, in newspaper articles and women's magazines. Now members of her own community are threatening to kill her – and her mother thinks they're right.

At 23, her first book now tops the country's bestseller list – an autobiographical novel praised by critics nationwide. She has been featured in interviews on TV, in newspaper articles and women's magazines. Now members of her own community are threatening to kill her – and her mother thinks they're right.

This isn't in Iran, or Saudi Arabia, or Iraq. This is happening in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, that alleged bastion of tolerance and freedom.

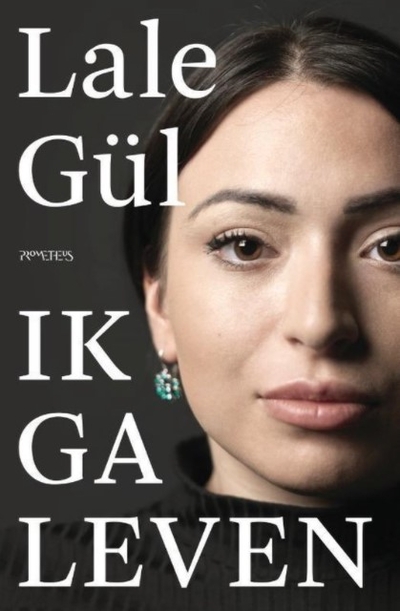

Lale Gül, the daughter of Turkish immigrants to the Netherlands, penned Ik Ga Leven (I Shall Live! ) to raise the curtains on what she calls "a look into my culture" through the eyes of a young woman who, like Gül herself, lives a kind of double-life: a young, freewheeling and independent Western girl in the outer world, a dutiful, pious Muslim daughter at home. Through the character of "Büsra," Lale Gül (pronounced "Lah-leh Guuyl") decries the oppressiveness of the community and culture in which she has been raised, a family in which she was forbidden to wear jewelry or makeup, to join school field trips without a male family member, to be friends with a boy, especially one who was not Turkish.

Like "Büsra," Gül's own parents are deeply pious, especially her mother, who, she says, fully supported October's beheading by a Muslim terrorist of French history teacher Samuel Paty in a Paris suburb. Paty's mortal sin: he had shown his students a caricature of the Prophet Mohammed. It is a perspective Gül finds deeply troubling, based on values she cannot herself embrace.

Indeed, according to the Dutch newspaper the Volkskrant, Gül began wrestling with Islam early, struggling to reconcile the lessons she learned in Quran school with what she studied in her elementary and high school classes: When she asked [in Quran school] why girls had to cover their heads and boys not, she told the Volkskrant, the teacher claimed the question "had been whispered to her by the devil."

This is the perspective she brought to Ik Zal Leven, as she recreated the tensions in her family, her fury at her mother, at her religion, at the stranglehold both have held her in through her entire life. Naively, she admits now, she thought her parents would never really know what she'd written. Her mother is illiterate. Neither parent speaks or reads much Dutch.

What she didn't count on was the effect of the publicity, and the rapid spread of tales throughout a small community like her own. A young, successful novelist – a Muslim woman, at that, and beautiful, with a controversial tale to tell – she was a perfect subject for the media.

But after one particular TV appearance, as one critic wrote, it was "as if a bomb exploded in her parents' community."

True, it didn't help that "Büsra" described her mother as a "carbuncle." But that wasn't the real problem. The real problem was her combat with orthodox Islam, with the questioning of a culture in which, as "Büsra" puts it, girls are forced to live "like houseplants" and become "breeding hens" once they are forced into a marriage. "Is this what I live for?" "Büsra" muses. "Is God then happy with my tragedy?"

The real problem, in short, is that Lale Gül dared to question the very principles of Islam and the culture in which she was raised.

Phones rang in the Gül household the day after her appearance on a talk show in early February. Lale's parents listened, horrified, to friends and relatives explaining to them what their daughter actually had written, how she had exposed their private life to the outer world, how she had spoken against their faith. Some of what her parents heard was untrue, just as much of the talk was on the street. An uncle threatened "to punch my teeth out of my mouth," she told the Volkskrant. And her mother, Lale says, defended him. "I can't say he's wrong," she says her mother told her. "You asked for it with that book."

That wasn't the only time her mother expressed violent wishes against her own daughter. "I understand that people want to strangle you," Lale's mother told her, according to an interview in Amsterdam daily Het Parool. "If you weren't my child, I probably would have strangled you, too."

Worse, still, the young author faces a barrage of threats from strangers, both online and on the street. She rarely leaves home now, fearing for her safety. She declined to be interviewed for this article, fearing further threats. She has been vilified in Turkey thanks in part to a tweet from former Geert Wilders ally Arnoud van Doorn, now an orthodox Muslim and leader of his own anti-Semitic political party, alleging that she had left Islam, and was proud of it. The tweet was translated into Turkish.

Some of this furor has been nearly humorous: in response to Van Doorn, Gül asked him to remove his tweet, calling him a "dirty dog." Van Doorn then filed a police complaint against her, saying the words "dirty dog" had "offended" him.

But little else is funny. Gül believes it will no longer be possible for her to visit Turkey as a result of Van Doorn's actions. She relies on her brother to protect her. She has been advised to take on a bodyguard, though to date she has rejected the idea. Fans compare her to activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the former Dutch parliamentarian and ex-Muslim who has been an outspoken advocate for the rights of Muslim women and for ex-Muslims worldwide. She waves off the comparison, calling Hirsi Ali her "hero."

Now, while Gül holds to her principles, proud that she has provided a glimpse into the world she and so many other young Muslim women are forced to live in, it is clear the pressure has taken a toll. She had considered leaving home, but decided against it. "I would no longer have a family," she told Het Parool. "So I am trying just to make clear by staying that no, I won't leave you, because I love you, and I hope one day you also will love me."

She has also made concessions, as have her mother and father. She agrees now to marry a Turkish man, though, she says, he will have to be as progressive-thinking as she is. And although she had planned a sequel to Ik Zal Leven, she will write no more books, at least none like this one.

Still, while there may be no more future for "Büsra," it is hard to imagine the same will be true for Lale. Her own passion for justice, it appears, will not so easily be silenced.

Abigail R. Esman is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands. She is the author of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West( Praeger, 2010). Her new book, Rage: Narcissism, Patriarchy, and the Culture of Terrorism, was published by Potomac Books in October 2020. Follow her at @radicalstates.

Copyright © 2021. Investigative Project on Terrorism. All rights reserved.