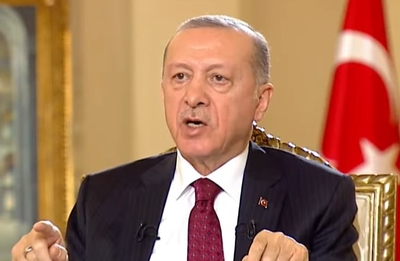

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan informed the country Saturday that he and his wife had tested positive for Covid-19. It was big news, as it would be coming from any world leader. Nonetheless, it is probably best not to say too much about it.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan informed the country Saturday that he and his wife had tested positive for Covid-19. It was big news, as it would be coming from any world leader. Nonetheless, it is probably best not to say too much about it.

Not, anyway, if you happen to be Turkish.

Which is what a woman known only as "Pinar O" quickly learned on Sunday, when the courts placed her under house arrest on charges of "insulting the president." Pinar had posted on Twitter using the hashtag #helva (halvah), a sweet often served in Turkey at funerals; the assumption made by officials, apparently, was that she was pleased to hear Erdogan was ill. (Pinar told the court she had intended the post for her boyfriend.) She was one of four people arrested that day, all for social media posts referring to Erdogan's diagnosis.

But that wasn't all.

On Monday, officials issued another arrest warrant, this time for former national swimmer Derya Buyukuncu, for tweeting, "There is a coronavirus and we pray. We pray, don't worry. I started making 20 pots of halvah. I will distribute it to the whole neighborhood when the time comes." Buyukuncu, however, no longer lives in Turkey, and so is not likely to be detained.

While the arrest of a private citizen for her social media posts is extreme, the prosecution of public figures like Buyukuncu for crimes of "insulting" the president – or, alternatively, insulting religious figures or ideas – has grown commonplace in Turkey under Erdogan's rule. Now, as his popularity slips, weighted by the country's latest economic crisis, the pace of such arrests appears to be accelerating.

Take, for instance, the arrest in late January, of a well-known TV journalist, Sedef Kabas, at her home in the middle of the night. Her crime: quoting an old proverb during her broadcast, which she later posted to her Twitter account: "When the ox comes to the palace, he does not become a king, but the palace becomes a barn." Officials claimed the remark was meant to insult President Erdogan, a crime that carries a prison sentence of one to four years.

"This offense will not go unpunished," Erdogan declared soon afterwards in a televised interview. "It is our duty to protect the respect of my function, of the presidency. It has nothing to do with freedom of expression."

Neither, apparently, did the lyric of a 2017 song by popular "pop music diva" Sezen Aksu, which Erdogan discovered that same week. The line in question, "Give my regards to the ignorant Eve and Adam," was, for Erdogan and other hard-liners, equivalent to blasphemy. "No one may insult the prophet Adam," he said. "Should anyone do this, it is our duty to rip off their tongue. Nobody is allowed to attack Eve, either. If someone does, we must show them their boundaries."

Aksu, who is said to have set the foundations of Turkish pop music in the 1970s, and remains at the top of the charts according to Turkey's Ahval News, immediately responded with a new song. Within hours, her newly-written lyric, "You cannot rip out my tongue/We'll see who'll stay/and who'll go/Because I am everyone," had been translated into more than 40 languages.

It only stoked Erdogan's fury. That same day, he issued a decree that promised to take "decisive steps" against "overt or covert activities through the media aimed at undermining our national and moral values and disrupting our family and social structure."

The edict turned up the power of Turkey's media watchdog, RTUK, which had already fined several TV stations for broadcasting "erotic" music videos or content that the organization claims makes positive LGBTQ references.

Critics of the move have since blasted Erdogan for the order. "When you look at the greater picture in Turkey and take into account the recent attacks on the freedom of expression and efforts to polarize society between conservatives and liberals, this seems to be the last piece of the puzzle," human rights attorney Veysel Ok told Al Monitor. "The intention is to instill fear so that no one dares raise a critical voice ... I fear it is a harbinger of more investigations, controls and closures toward the independent media."

It is a reasonable concern. In the latest World Press Freedom Index, Turkey rated 153rd out of 180 countries, three spots below Russia.

It doesn't stop with the media and the arts. On Feb. 2, the Council of Europe passed an interim resolution to bring the Turkish government before the European Court of Human Rights over its treatment of philanthropist Osman Kavala, who has been held awaiting trial since 2017. The Council cited a 2019 European court ruling that there was insufficient evidence to hold Kavala, and the Erdogan government had "pursued an ulterior purpose, namely to silence him and dissuade other human rights defenders."

Disputes about Kavala's fate prompted Erdogan to expel ambassadors of 10 countries – including the United States – briefly last October. And while he was officially acquitted in 2020 of participation in the 2013 Gezi uprising, the government raised new charges against him within hours of his release, contending (without evidence) that he had been involved in the failed coup of 2016.

In the end, all this seems to be sending Turkey's president careening into a collision course with Europe and the West. As the Council of Europe calls Kavala's detainment "a worrying precedent [that] increases the EU's concerns regarding Turkish judiciary's adherence to international and European standards," Erdogan is clamping down on any threat to his power, and to the religious values shaped by his form of anti-Western, conservative Islamism. In what increasingly seems an irreconcilable conflict, he may soon find that Sars-CoV-2 is the very least of his problems.

IPT Senior Fellow Abigail R. Esman is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands. Her new book, Rage: Narcissism, Patriarchy, and the Culture of Terrorism, was published by Potomac Books in October 2020. Follow her at @abigailesman.

Copyright © 2022. Investigative Project on Terrorism. All rights reserved.