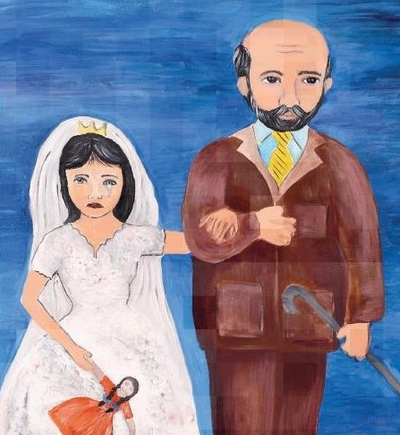

UNICEF image |

But by the time the photo session ended, the little girl was married. It hadn't been a game at all.

Her father's friend, 29-year-old Kadir Istekli, was her new husband. And she was only 6 years old.

Now 24, that girl – known only by her initials, HKG – is pursuing a criminal case against both Istekli and her father, Yusef Ziya Gumusel, who had arranged the marriage. The trial resumes tomorrow.

The case has created significant uproar in their native Turkey, where Gumusel is a leading figure in the Islamist Ismailaga Brotherhood, considered by many to be a cult. With over 100,000 members, the Brotherhood – based in Istanbul's Fatih district – also is said to have ties to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his ruling AKP party.

Politicians from the opposition parties have condemned the marriage and sexual abuse of HKG and other girls in this and other religious sects as prosecutors call for a 27-year sentence to be imposed on each of HKG's parents and Istekli, with an additional 40-year sentence for Istekli for sexual assault. Meanwhile, the Ismailaga community is calling for the journalists who first broke the story last December to be arrested. Sentencing in the case is scheduled for May 22 – one week after Turkey's May 14 presidential elections, which many see as the most significant in the 100-year history of the Republic.

HKG's story is particularly horrifying: the journalists who first reported it uncovered evidence that she was sexually abused from the start of the marriage, and she has said that it was not until she was 18 that she first realized that it was not normal for 6-year-old girls to be wedded off – a discovery she claims she made only when she looked it up on her phone.

Moreover, her father warned her repeatedly against disobeying her husband and when she first attempted to escape, he found her, beat her, and sent her back home to Istekli. In November, 2020, however, HKG finally fled her marriage and filed charges against her husband and both parents.

But while hers was an especially shocking case, child marriages are not uncommon in Turkey, which has one of the highest rates of child marriage in Europe. Approximately one-third of all Turkish women marry before the age of 18. And sects such as the Ismailaga Brotherhood, a highly conservative Sunni Sufi group, are arguably a large contributor to the trend. Indeed, many Turks maintain that the Ismailaga's strong influence on Turkey's ruling party was behind the country's 2021 withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence.

That influence, and the suspected ties between Erdogan and the AKP and Ismailaga and other Islamist groups, may well have consequences for the upcoming elections. Already, opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu, who leads Erdogan in the polls, has accused justice officials and the Minister of Family and Social Services of neglect and complicity, noting it took a full two years to arrest Istekli and Gumusel after HKG filed charges.

"Who have you been hiding behind for two years?" Kilicdaroglu demanded, speaking to reporters during a demonstration in support of HKG. "Do the people you take photos with put pressure on you to cover up this incident?" Members of Ismailaga are frequently photographed with AKP party members, and Erdogan himself wrote the official obituary for the Brotherhood's founder, Sheikh Mahmut Ustaosmanoglu (aka Mahmut Effendi) when he died last June, aged 93. The two had often been photographed together.

Yet for many young girls, matters are only getting worse. In February, Turkey's religious body, the Diyanet, decreed that those who adopt the orphaned children of earthquake victims can freely marry them. According to the fatwa, "The relationship between the adopter and adopted child does not create a barrier to marriage." Under Islam, stated the Diyanet, adopted children are not able to inherit from their adoptive parents; marriage could be a way to skirt the problem.

The edict followed a 2018 declaration that, in order to prevent sexual relations or pregnancy occurring out of wedlock, girls as young as nine could marry in religious ceremonies. The minimum legal age for marriage for girls in Turkey is supposed to be 16, and then only with parental permission.

Taken together, and especially with the withdrawal from the Istanbul charter, these events threaten to further harm Erdogan's reelection bid at a time when he is already struggling in the polls. A weak economy, record-high inflation, ongoing concern about the influx of Syrian and North African refugees, and the horrors of the recent earthquake in Eastern Turkey – combined with his government's poor management of the aftermath – have already taken a heavy toll on his popularity. And in recent personal conversations, many non-religious women who had remained loyal to Erdogan for economic reasons, expressed misgivings, citing concerns about women's rights and freedoms and the AKP's increasingly apparent ties to radical groups like Ismailaga.

True, in the face of public outrage, the Diyanet ultimately retracted its statement on marrying earthquake orphans. Nonetheless, the edict left no doubt where the country is headed should Erdogan win the May election – and it once again makes clear, as such things so often do, that a vote to preserve the rights of women is a vote to preserve democracy itself.

IPT Senior Fellow Abigail R. Esman is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands. Her latest book, Rage: Narcissism, Patriarchy, and the Culture of Terrorism, was published by Potomac Books in October 2020. Follow her at @abigailesman.

IPT Senior Fellow Abigail R. Esman is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands. Her latest book, Rage: Narcissism, Patriarchy, and the Culture of Terrorism, was published by Potomac Books in October 2020. Follow her at @abigailesman.

Copyright © 2023. Investigative Project on Terrorism. All rights reserved.