Profile

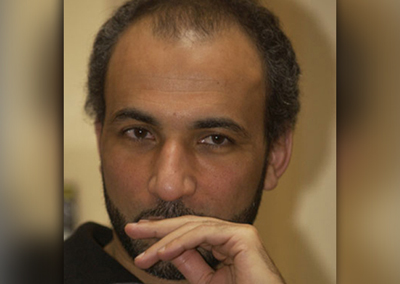

Tariq Ramadan

Tariq Ramadan, a Swiss citizen, has degrees in philosophy, religion, and Islamic studies, having obtained this last degree from Al Azhar Islamic University in Cairo.[1] Tariq's father, Said Ramadan, founded the Islamic Geneva Center in 1961, which is currently headed by Tariq's brother Hani.[2] The center became "a launching pad" for Muslim Brotherhood expansion and worked with Bank Al Taqwa,[3] which later would be designated by the U.S. as a specially designated global terrorist entity for providing a clandestine line of credit to a close associate of Osama bin Laden.[4]

Tariq's father was a well known Islamist and his grandfather was Hassan al Banna, the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood.[5] Tariq's genealogy played a crucial role in his fame as a religious scholar and community leader. His books and videotapes are widely distributed and he is a popular authority on Islam with the European and Arab media. In the mid-1990s, Tariq Ramadan was banned from entering France for suspected links with Algerian extremists, but the ban was lifted shortly thereafter.[6]

The Department of Homeland Security revoked Ramadan's visa in July 2004, preventing him from taking a teaching position at Notre Dame University in South Bend, Indiana.[7] Ramadan once made a financial contribution to a French charity linked to Hamas, the charity "Comite de Bienfaisance et de Secours aux Palestiniens" (CBSP), which was blacklisted by the US Department of the Treasury in 2003.[8]

In October 2005, Ramadan began teaching at St. Antony's College at the University of Oxford on a Visiting Fellowship.[9] He was also invited in 2005 by the British government to join the Home Office Working Group on Tackling Extremism.[10]

Ramadan now is able to visit the United States, after Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton signed an order allowing Ramadan to obtain a visa.[11] He remains a controversial figure both in France and the United States. Ramadan has been accused by some, including French author Caroline Fourest, of taqia, or engaging in double-talk.[12] His comments on 9/11 were very equivocal, playing on arguments usually advanced by conspiracy theorists, such as: "Who profits from the crime?" [13]

In a lengthy article in the New Republic, liberal professor Paul Berman detailed the criticism of Ramadan's views and the criticism they foster. More than half a dozen French writers have published books on Ramadan's ideas, some finding him a resourceful speaker who adapts his lectures to the attending audience. He also has often been accused of being an Islamist, anti-Semitic, and sexist. He has drawn severe criticism from numerous Western public figures, ranging from scholars and journalists to political, religious, and community leaders.[14]

Some of those critics "suspect that clandestinely Ramadan, too, entertains the larger pop-eyed more-than-theological project: a world dominated by Islam, with his Muslim counterculture serving as the future empire's fifth column within Europe, under the ultimate control of the Muslim Brotherhood," Berman wrote.[15]

In 2003, Ramadan drew criticism for a televised debate with current French President Nicolas Sarkozy. Sarkozy challenged Ramadan for an opinion about whether adulteress Muslim women should be stoned to death, as Islamic law dictates. Rather than condemn the practice, Ramadan advocated a moratorium in order to "open a debate and to show that there is a great deal of disagreement between the scholars."[16]

[1] "Tariq Ramadan," Penguin Books Website, http://www.penguin.co.uk/nf/Author/AuthorPage/0,,1000071815,00.html (Accessed August 20, 2007).

[2] Andrew Hussey, "NS Profile - Tariq Ramadan," New Statesman, June 1, 2004, http://www.newstatesman.com/200406210020 (Accessed August 20, 2007).

[3] Robert Dreyfuss, "Cold War, Holy Warrior," Mother Jones, January/February 2006.

[4] Olivier Guitta, "Danger: Tariq Ramadan is coming to the US," American Thinker, http://www.americanthinker.com/2004/05/danger_tariq_ramadan_is_coming.html, May 3, 2004 (Accessed August 20, 2007).

[5] Nicholas La Quesne, "Trying to Bridge A Great Divide," Time, http://www.time.com/time/innovators/spirituality/profile_ramadan.html (Accessed August 20, 2007).

[6] Olivier Guitta, "Tariq Ramadan is not a victim," December 22, 2004, http://www.americanthinker.com/2004/12/tariq_ramadan_is_not_a_victim.html (Accessed August 20, 2007).

[7] PR Newswire, September 22, 2004.

[8] See for example "Why Tariq Ramadan lost," The Washington Times, October 11, 2006

[9] "Biography," Tariq Ramadan Website, August 22, 2004, http://www.tariqramadan.com/rubrique.php3?id_rubrique=13 (Accessed August 20, 2007).

[10] Vickram Dodd, "Blair backs banned Muslim scholar," The Guardian, August 31, 2005, http://politics.guardian.co.uk/terrorism/story/0,15935,1559554,00.html (Accessed August 20, 2007).

[11] Exercise of Discretionary Authority under Section 212(d)(3)(B)(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, signed by Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, January 20, 2010.

[12] Paul Berman, "Who's Afraid of Tariq Ramadan," The New Republic, June 4, 2007

[13] Nicolas Geinoz, "Ben Laden, coupable idéal?" La Gruyere, September 22, 2001.

[14] Paul Berman, "Who's Afraid of Tariq Ramadan," The New Republic, June 4, 2007.

[15] Paul Berman, "Who's Afraid of Tariq Ramadan," The New Republic, June 4, 2007.

[16] "Pulling Up the Welcome Mat," (WebChat) Chronicle of Higher Education Website, September 9, 2004, http://chronicle.com/colloquylive/2004/09/ramadan/ (Accessed August 20, 2007).